Complaints of vaginal irritation and/or vaginal discharge are very common in ambulatory settings, particularly in gynecology offices. Bacterial vaginosis, candidiasis, and trichomoniasis account for about 70% of these complaints. Patients who present with these symptoms are frequently over-treated and misdiagnosed. Those with recurrent symptoms are especially challenging. Here are four tips for correctly diagnosing women with symptoms of vaginitis.

1. Check the pH.

Testing the vaginal pH is often under-utilized in clinical practice. Many providers either rely almost exclusively upon history for the diagnosis of vaginitis or other ancillary tests that are non-specific. The differential diagnosis for symptoms of vaginal irritation and discharge is long and includes physiologic discharge, herpes, atrophic vaginitis, gonorrhea, chlamydia, desquamative inflammatory vaginitis, vulvodynia, vulvar dystrophy, vulvar dermatitis, retained foreign bodies, non-Candida albicans yeast infections, in addition to the big three: vulvovaginal candidiasis, bacterial vaginosis, and trichomoniasis.

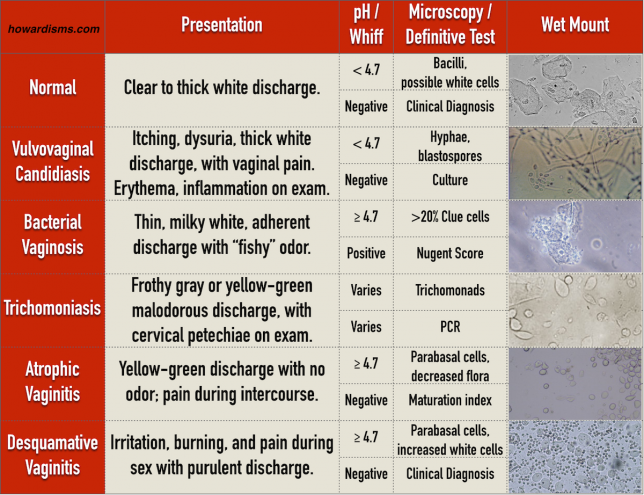

Determining the vaginal pH is a valuable first step in narrowing down the differential diagnosis. A normal vaginal pH is < 4.7; anything ≥ 4.7 is considered abnormal. Women with vulvovaginal candidiasis, genital herpes, vulvodynia, vulvar dermatitis, and a physiologic discharge will have a normal vaginal pH. Women with bacterial vaginosis, atrophic vaginitis, desquamative inflammatory vaginitis, cervicitis, and other conditions, will have an elevated pH. The presence of blood, semen, cervical mucus, and amniotic fluid will also result in an elevated vaginal pH. For women with trichomoniasis, the vaginal pH may be normal or abnormal.

In addition to helping narrow down the differential, knowing the vaginal pH is also essential to diagnosing bacterial vaginosis (see Tip #2).

2. Don’t rely on a test to diagnose BV.

BV is a clinical diagnosis; it should not be diagnosed based upon a test result. This occurs sometimes with Pap smear results that show a shift in flora consistent with BV and it also occurs frequently today with PCR based tests for Gardnerella vaginalis. But the clinical diagnosis of BV should be based on Amsel’s criteria, which requires that the patient have a three of four findings:

- elevated vaginal pH

- positive whiff or amine test

- abnormal gray discharge

- greater than 20% clue cells on saline microscopy

The presence of Gardnerella vaginalis detected by culture or PCR does not indicate that the patient has BV; similarly, the absence of Gardnerella vaginalis does not mean the the patient doesn’t have BV. Women with a clinical diagnosis of BV may have infection with any of a number of bacterial species, including Atopobium vaginae, Prevotella, Bacteroides, Peptostreptococcus, and several others. Reliance upon the presence of Gardnerella vaginalis for diagnosis may lead to under-diagnosis of BV due to the condition being caused by other bacteria. Unfortunately, as these tests have become commercially available they’ve been introduced into practice without scientific evidence. Providers increasingly forego valuable clinical testing, skipping not only the vaginal pH but also the whiff test. The whiff test will usually be positive only with bacterial vaginosis and, in some cases, trichomoniasis.

3. Don’t treat normal discharge.

For many providers, any complaint of a white and bothersome discharge is treated as yeast. If the symptoms don’t improve, then recurrent or resistant disease is suspected and treated. But in many cases the discharge that’s noticed is normal and physiologic. Physiological discharge ranges from a clear mucus in the mid cycle to a thick white discharge at other times that is frequently mistaken for candidiasis. During menses, the discharge may even look purulent and be mistaken for cervicitis. Physiologic discharge is a diagnosis of exclusion. The patient should have a normal vaginal pH, a negative whiff test, and Lactobacillus present on saline microscopy. The amount of discharge and consistency will vary with different methods of hormonal birth control. Many patients will need to see evidence of a negative culture to be convinced that their discharge is normal. About 10% of women with chronic or recurrent vaginal complaints simply have physiologic discharge.

Since physiologic discharge is a diagnosis of exclusion, don’t forget to exclude chlamydia, gonorrhea, trichomoniasis, and at least consider rare causes of chronic discharge like vesicovaginal fistula or fallopian tube cancers. Don’t get in the mindset that everything that is white is yeast, everything yellow-gray is BV, and everything green is trichomoniasis, or in the mindset that everything that itches is yeast or everything that smells like fish is BV. These clues help aid in diagnosis, but basing treatment primarily on these clinical symptoms often leads to the wrong diagnosis. In some cases, this means that patients are convinced that their normal cervical discharge is a yeast infection requiring treatment; in other cases, it means that patients believe that their atrophic vaginitis or lichen sclerosis is simply a yeast infection. Patient are harmed in both cases.

4. Think outside the box.

Most misdiagnosis happens because of a limited differential diagnosis followed by premature closure or confirmation bias. For example, a patient presents with itching and the physician thinks yeast. She then sees thick white discharge on exam and treats the patient for yeast, ignoring the fact that there are no yeast present on wet mount. The treatment may be appropriate: it is possible that there are no yeast on the wet mount due to a false negative test. But it is also possible that the thick white discharge is a physiologic discharge and that there is another, undiagnosed reason for the itching. More than 1/3 of women who present with symptoms of vaginitis don’t have one of the big three (trich, BV, yeast). This means that if you always seem to be diagnosing one of those three, you are very often wrong. So, consider the possibilities:

- Acute itching: Candida (typical and atypical), BV, Trich, Group A Streptococcus, scabies, pediculosis pubis, contact dermatitis.

- Chronic itching: Contact or allergic dermatoses, atopic or seborrheic dermatoses, psoriasis, lichen sclerosus, planus, or simplex chronicus, atrophic vaginitis, vulvar or vaginal premalignancy or malignancy.

- Prepubertal discharge: Retained foreign body, sarcoma botryoides, pinworms, sexual abuse.

- Reproductive age discharge: Yeast, BV, Chlamydia, Gonorrhea, Trichomonas, PID, herpes cervicitis, cervical, uterine, or fallopian tube cancers, foreign bodies, contact or allergic dermatoses, fistulae.

- Postmenopausal discharge: Atrophic changes (genitourinary syndrome of menopause), pyometria, genital tract malignancies, fistulae.

- Vulvovaginal pain: Lichen planus, sclerosus, or simplex chronicus; vulvar vestibular syndrome, herpes, contact and allergic vulvar dermatoses, vulvar eczema, yeast, psoriasis, vulvar varicosities, pudendal neuralgia, etc.

What else?

- If you suspect yeast and the culture is negative, repeat the culture again before excluding yeast as the diagnosis.

- If a patient has recurrent yeast, consider atypical species which will need other treatments and also consider immune compromise (diabetes, HIV, etc.).

- Don’t be afraid to do a punch biopsy, particularly in menopausal-aged women, who present with vulvar pain or itching.

- Vaginal estrogen therapy may help women of all ages, from premenarchal girls with vulvovaginitis to menopausal women with the genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Reproductive-age women, particularly those on low dose estrogen birth control pills, may also benefit from vaginal estrogen therapy for chronic vaginitis symptoms or pain during sex.