Pregnancy tests come in three varieties: a urine qualitative test (it’s either positive or negative), a serum qualitative test (again, either positive or negative), and a serum quantitative test (with a specific numeric result). I see far too many serum quantitative hCGs ordered in clinical practice (by OBs, ER docs, etc.) and this implies that many clinicians don’t understand when to order a quant hCG and how to interpret it. There are lots of myths surrounding the appropriate use and interpretation of quant hCGs, so here are four tips to help you better utilize a quantitative hCG.

1. Don’t order one in the first place.

Most of the errors I see involve ordering a quant hCG when it is unnecessary. Be clear why you are ordering it and how it might affect the management of the patient.

- If you simply want to know whether or not a person is pregnant with a normal, intrauterine pregnancy, you’re better off with just a simple urine pregnancy test. A urine pregnancy test is more specific for a normal, intrauterine pregnancy than a blood test of either variety. Why? Because it usually won’t be positive if the hCG is around 25 or less and therefore it won’t produce as many false positives. Don’t waste time or money on a quantitative hCG.

- If you would like more sensitivity for an early pregnancy, a serum qualitative test will be just fine. It will detect lower levels of hCG from serum than from urine and it will be reported quickly (unlike a serum quantitative). In practical terms, though, the difference in a positive urine versus a positive serum is only a day or so. Correlate this with the clinical history; it is unusual that the difference in a day or so will make matter for the patient.

Here are a couple of clinical examples where quant hCGs are ordered unnecessarily:

- A patient presenting to the ED with an already established, ultrasound-visible pregnancy does not need a quant hCG. If she presents with bleeding or symptoms of miscarriage, the sole clinically important issue is whether there is still a viable intrauterine pregnancy that comports with what has already been established by a previous US (and perhaps her blood type in case she needs anti-D antibody). Her quant hCG is completely irrelevant and is a waste of both time and money.

- A patient undergoing surgery or radiographic procedures doesn’t need a quant hCG. Again, a urine or serum qualitative test is faster and more specific for an early intrauterine pregnancy than a quant hCG.

2. Don’t believe in the doubling every 48 hours rule.

Far too often the reason a quant hCG is ordered is because the provider believes it can help navigate the waters of a threatened abortion. This is based upon the idea that the hCG value should double roughly every 48 hours in a normal pregnancy. This might be a useful strategy if you have two values in sequence (ideally about 48 hours apart) to observe the trend in a pregnancy too early to detect by US (before about 5 weeks). If the number is going up (roughly doubling over 48 hours, but at least rising by about 53%), then this observation is reassuring that there is a continuing pregnancy, though it could just as well be an ectopic, a molar pregnancy, or normal intrauterine pregnancy. If the number is declining, this often indicates a miscarriage (though it might also decline temporarily due to a vanishing twin pregnancy). If it is plateauing, it might indicate an ectopic, miscarriage, or even an early intrauterine pregnancy (again, perhaps with a vanishing twin).

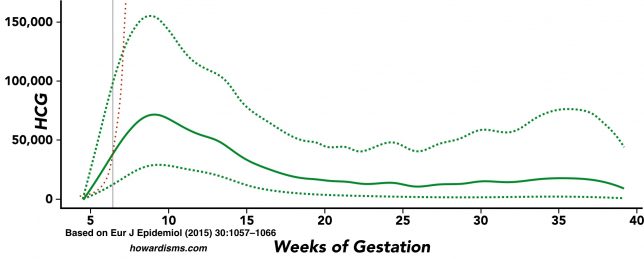

However, the time in which a quant hCG will double every 48 hours is very limited. Look at the chart below. The solid green line represents the average quant hCG over the entire length of a singleton pregnancy, and the dotted green lines are plus/minus two standard deviations. The dotted red line represents a theoretic hCG value that doubles every 48 hours. Notice that the average hCG of the average pregnancy grows at a slightly faster rate until about 6 weeks gestation, then, grows at a significantly slower rate until about 9 weeks, after which it declines. Also note the wide variation in hCG values around the median value. Where the gray line intersects the median value at about 6 weeks indicates the point in pregnancy where relying on a doubling hCG every 48 hours is clinically useless and may lead to inappropriate management.

In other words, don’t use a quant hCG after 6 weeks of pregnancy (unless you are using it to follow a mole or an ectopic). Unfortunately, I see quant hCGs ordered well beyond this gestational age regularly (particularly in the ER, and the patient is then instructed to present to the OB for a repeat value in 48 hours.

3. Understand when to use hCG and when to use ultrasound to manage early pregnancy problems.

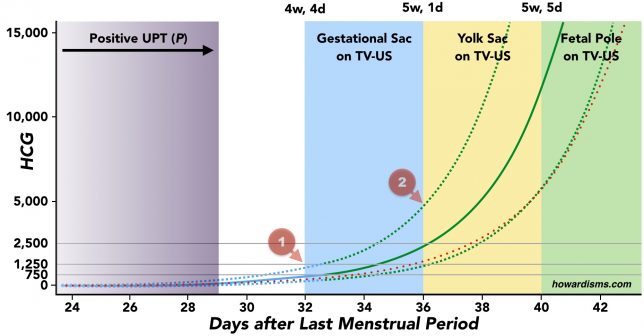

Practically speaking, at a certain point in the pregnancy, the only thing that really matters is the ultrasound. Look at the graph below to understand what can be seen on ultrasound and when. Again, the solid green line represents the average hCG for a singleton pregnancy and the dotted green lines represent plus or minus two standard deviations. The dotted red line represents a theoretic 48 hour doubling hCG. Again, note that the average hCG doubles more quickly than every 48 hours early in pregnancy.

The probability of a positive urine pregnancy test increases from near zero at about 3 weeks and 2 days after the last menstrual period to nearly 100 percent by 4 weeks and 1 day after the last menstrual period (purple zone). With modern transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS), a gestational sac can be seen as soon 4 weeks and 4 days (blue zone), but this early sac will be small (1-2mm) and can be easily missed or could represent something else, like blood or a pseudosac. At roughly 5 weeks and 1 day (yellow zone), a yolk sac can be seen with TVUS; the presence of a yolk sac much more reliably predicts an intrauterine pregnancy than a gestational sac alone (though heterotopic pregnancies are still a possibility). By 5 weeks and 5 days (green zone), a fetal pole (about 2 mm) with cardiac activity can be visualized with TVUS.

The value of a quant hCG is really limited to two cases:

- There is nothing visible on the TVUS when you clinically expect there to be.

- There are worrisome symptoms (pain, bleeding) before the time one would expect to see anything on TVUS (roughly five weeks).

We will deal with the first case in the next tip. The second case, however, is the most frequent legitimate use of a quant hCG. For example,

- A patient presents four weeks after the LMP with bleeding. TVUS is of no value because there is no expectation that anything should be seen on US at this gestational age. It is reasonable to order a quant hCG and repeat the value in two days. If it rising appropriately, plan for an TVUS in 1-2 weeks. If it is dropping, plan for a urine hCG in two weeks to confirm miscarriage. If the result of the first quant hCG is above the discriminatory threshold (see the next tip), then proceed with a TVUS.

4. Understand how to use the discriminatory threshold.

A discriminatory threshold is the level of hCG at which something should be seen on TVUS or one might presume that the pregnancy is abnormal. This concept is particularly important for early detection of ectopic pregnancy.

The exact value of a discriminatory threshold is debated and has changed considerably over the years. The value has changed for three reasons:

- We currently use a different laboratory definition of hCG than was used in the past (that is, a different standardized comparator).

- TVUS has become much more sensitive to small pregnancy structures (that is, we can see things earlier today than we could 10-20 years ago).

- We now focus on the 99th percentile as an upper limit instead of the 85th percentile. Previous published studies gave the median hCG and the 15th and 85th percentiles; the threshold was set at the 85th percentile, but using the 85th percentile meant that 15% of pregnancies would be missed. Since ectopic pregnancies constitute about 1% of pregnancies, then using the 99% percentile still allows for early detection of most ectopic pregnancies but doesn’t potentially harm 14% of normal pregnancies.

The dotted green lines in the graph above represent the values that are plus or minus two standard deviations from the median, not the top and bottom 1 percentile, but the values are almost the same. Note at the red indicator 1 the intersection of the dotted line with the blue box indicating the ability to visualize a gestational sac. This occurs at roughly 1,200. Notice that you might see a gestational sac with a much lower hCG, as low as 300; but the discriminatory threshold doesn’t tell us the best case or average case scenario, it is meant to tell us the worst case scenario. Similarly, red indicator 2 represents the discriminatory threshold for the presence of yolk sac.

So should we use 1200 as a discriminatory threshold for treating ectopic pregnancy? No. ACOG recommends not proceeding with medical treatment of ectopic unless the hCG is above 3,500 or unless there has been a trend that shows an inappropriate rise. Why 3,500 instead of 1,200? Because in real life, the quality of the ultrasound varies and patients might have an early twin pregnancy or a vanishing twin pregnancy. Before giving methotrexate, there needs to be a high degree of certainty that a normal singleton (or twin pregnancy) isn’t being treated. This means that 1,200 is too low.

It is important to remember this: The gestational age is a more reliable indicator of what you should expect to see on TVUS than the quant hCG. Far too often, clinicians focus on the discriminatory threshold and ignore other clinical indicators. I know that I should expect to see a heartbeat at 5 weeks and 5 days (whether twin or singleton), but the hCG might be anywhere from 5,000 to 25,000 (or even higher if twins or triplets). I expect to see a a GS at 4 weeks and 4 days but the hCG might range from 300 to 3,000. Thus, it is very important to attempt to clinically date the pregnancy and correlate this with hCG and TVUS findings. Consider each of the following:

- When was the LMP? Was it normal?

- Are her periods regular? Was she on birth control at the time of conception?

- When did she first have a positive test? Had she had a recent negative one?

- When did the first symptoms of pregnancy occur (breast tenderness in particular)?

- Has there been any bleeding which might indicate passage of material before you’ve seen her?

For example, if a woman presents and she is 7 weeks pregnant by a regular and normal LMP, and she had a positive home test three weeks ago, I expect to see something on US regardless of her quant hCG. But if she is 7 weeks by an irregular LMP and had a positive test two days ago, then a quant hCG might be helpful if nothing is seen on the TVUS. Read here for more on dating an early pregnancy.

What else?

Remember, multiples change everything. These graphs are only for singleton pregnancies. But because of multiples, using a discriminatory threshold of 3,500 to direct treatment with methotrexate makes senses. Twin pregnancies and ectopic pregnancies are of approximately equal likelihood clinically; so if you use 1,200 or 1,500 you are just as likely to give methotrexate to a normal twin pregnancy as an ectopic one.

Progesterone values aren’t really that useful. Don’t order a progesterone value with an early pregnancy unless it changes the management (hint: it shouldn’t ever change the management). It will not help you decide if a pregnancy is viable or not viable or intrauterine or not intrauterine. What’s more, progesterone supplementation is not science-based in cases of threatened or recurrent abortion and shouldn’t be done just because the progesterone level is low, whatever that means.