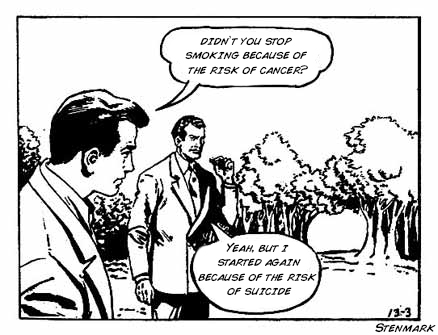

The ideal physician is not risk-averse but rather is a risk-mitigator. Risk is inescapable. We have to be able to understand risks in real terms and also be able to communicate those risks to patients in ways that matter. The risk-mitigator recognizes that each alternative has some risks but chooses to navigate through the risks in the best way possible. A risk-averse physician makes emotional decisions and reacts to boogeymen. By boogeymen, I mean those emotionally-laden (but perhaps very rare) risks, like guns, sharks, lightning, or uterine ruptures.

Quantification of risk is cognitively difficult. Human perception of risk is hard-wired for different types of risks than those we commonly encounter today. In our evolutionary past, we faced immediate and daily risks, like unsafe food or contaminated water sources, weather extremes, or protection from wild animals. But today’s risks are often incremental and more long-term. For example, the negatives of cigarette smoking or physical inactivity have to be measured over many years or decades to quantify them; and, even though we all cognitively appreciate those risks, we don’t react to them in the same way that we might react to a charging bear. This is especially true for the subtle risks and subtle benefits involved in medical decision making. It is very difficult for a person to comprehend why it’s worthwhile to do something (or to not do something) if it modifies the absolute risk of a negative outcome by only one in many thousands. But the majority of our medical decisions involve risks or benefits on this scale. To comprehend this scale, we need to think in terms of absolute risk reduction and use metrics like number needed to treat (NNT) or number needed to harm (NNH).

Risks of short term harm can be measured using micromorts, which is a unit representing a one-in-a-million chance of death. For example, sky-diving is equal to 9 micromorts per jump. Longer term (or cumulative) risks are better measured using microlives, which is equivalent to 30 minutes of lifespan. Smoking one pack of cigarettes reduces life expectancy by about 10 microlives, or 300 minutes.

Tools like micromorts and microlives or NNT or NNH are useful for understanding and communicating risks to patients; once a risk is properly understood, a patient can decide how valuable the intervention or lifestyle change might be, given her personal values. These tools help us mitigate risk, rather than have overly-emotional reactions to boogeymen. For example, if you ride 228 miles per year on a motorcycle or 380 miles on a bicycle, you will have equaled your personal risk of being killed with a gun in that same year. Yet the gun is more emotionally-weighted; so many people who ride motorcycles or bicycles also believe that gun violence is so bad that guns should be banned, though they would never say the same for motorcycles or bicycles. Of course, these measures don’t tell the whole picture. Riding a bicycle is exercise, and that exercise will increase your life-span by about 3 microlives (or 90 minutes) for each 60 minutes of riding. This benefit hopefully outweighs the risk of getting hit by a truck while riding your bicycle. So, too, a gun may save your life, and hopefully gun ownership outweighs the risk of gun death.

Comparing acute and chronic risks is more difficult, but consider this: smoking a pack of cigarettes per day for one month is equivalent to about 430 micromorts, which is equal to your risk of dying from a gun over ten years plus the risk of death from scuba diving, skydiving, hang-gliding, and riding on a jet for 27,000 miles combined! That’s just one month of smoking a pack per day. There are two lessons here: first, quit smoking; second, stop being afraid of boogeymen.

One more example: A mildly obese, pack-a-day smoker, who watches two hours of television per day accumulates a deficit 5,110 microlives per year, which is about 3.5 months of life expectancy. Ok; I’ve made my point.

Why do so many physicians tend to be risk-averse rather than risk-mitigators? Recently, we discussed the pejorative term “cowboy,” used in reference to physicians who are perceived as taking unwarranted risks. Most of the people who call others cowboys are strongly risk-averse practitioners. If you combine a general tendency towards being risk-averse with a poor understanding about the real risks and benefits of things that we do then you create an environment that is intolerant of even good risks.

Risk-averse providers often have a difficult time accepting the fact that there are an irreducible number of negative outcomes associated with life in general, medicine in particular, and obstetrics especially. Risk-averse people often distinguish between negative outcomes that happen without an intervention and those negative outcomes that happen after an intervention. Illogically, they more heavily weight the negative outcomes that happen after an intervention compared to those negative outcomes that happen without an intervention. This mindset is often influenced by medico-legal considerations. But a poor patient outcome is a poor patient outcome.

In other words, if a patient dies after a surgery, then the feeling is that the provider who performed the surgery exercised poor discretion and operated on a case that she should not have operated on; yet, if the same patient had died without intervention, then the same provider is lauded as caring and compassionate and letting nature take it’s course in an unfortunate circumstance. This type of risk-aversion also drives providers to avoid the sickest and most at-risk patients; that is, the patients most in need often have less access to care. Many OB/Gyn practices don’t accept patients who weigh above a certain amount, who use narcotics, or who have had a certain number of prior cesareans, for example.

If this type of harmful risk aversion doesn’t resonate as true to you, let’s consider the example of Lawson Tait. At the beginning of Tait’s career in the 19th century, death was the most likely outcome for a woman who suffered a ruptured ectopic pregnancy. There were no successful surgical or medical interventions described. Ectopic pregnancy, for the time, was relatively easy to diagnose: If a woman presented with delayed menses, and had pelvic pain with signs or symptoms of shock, she more than likely had a ruptured ectopic pregnancy and two out of three of these women died.

With no good treatment options, Lawson Tait was left with two choices: hope that the woman was lucky enough to be in the 1/3 of women who lived, or attempt surgical intervention. Tait was a forward thinking man. The epitaph on his tombstone is “Do the next thing.” So rather than wait and watch women die over and over again, he attempted surgical intervention. Unfortunately, his first operative patient died anyway. He improved the surgical technique and only one of the next 40 women died. His technique and the principle of early surgical intervention has saved countless thousands of women’s lives since his first case in 1883. He made many other ground-breaking contributions to surgery and women’s health. Today he is remembered, along with James Marion Sims, as the father of modern gynecology. But he was described by his peers as “dogmatic, bold, fearless … less than tolerant of orthodox thinking … coarse, swearing, gluttonous, and a rampaging bully.” Like Ignaz Semmelweiss, many of his contemporaries used ad hominem attacks to discount his work. To many of his contemporaries, he was a cowboy.

His peers were risk-averse. Tait, on the other hand, realized that there are good risks and there are bad risks. Tait was a risk-mitigiator. He was deeply affected by the case of a woman in 1881 who died of an ectopic after he chose to not operate on her. He challenged dogma and the status quo, and this was threatening to his peers. He went toe-to-toe with Joseph Lister as he advocated for asepsis in surgical technique, and though he was vilified at the time for it, he is now remembered as one of the most significant surgeons of all time.

A modern example of this type of risk-averse thinking is the attitude shared by a majority towards a trial of labor after cesarean delivery (TOLAC). Many small hospitals have made it nearly impossible to offer TOLACs to women who desire them. This commonly comes from non-obstetric providers, such as anesthesia, hospital administrators, or risk management personnel. Unfortunately, it is also pushed by Obstetricians who don’t want to perform VBACs. Patient counseling usually focuses on the boogeyman, that is the risk of uterine rupture and the consequences thereof, without really providing information about the risks of cesarean delivery of the current and future pregnancies.

Each of these risk-averse people are unwilling to accept a small increased risk in uterine rupture (the Boogeyman) to mitigate a larger risk (the risk of maternal death from repeat cesarean delivery or the risk of catastrophic uterine rupture from a home TOLAC). A woman who is browbeat into accepting a repeat cesarean delivery faces a 3.5-fold increased risk of death. If she is denied a hospital TOLAC, she may choose to try it at home. This practice is becoming much more commonplace and is readily endorsed by legions of homebirth attendants. If she attempts a trial of labor at home, and her uterus ruptures, her baby will almost certainly die and the mother too will be exposed to significantly increased risks.

In-hospital TOLACs are associated with an increased risk of perinatal mortality (130 per 100,000) compared to the risk with a repeat cesarean (50 per 100,000). Yet this increased of perinatal mortality with a TOLAC is comparable to the risk of perinatal mortality for a primigravida in labor in the United States. If we allow primigravidas to labor, then we should allow TOLACs. Why accept the increased risk of perinatal mortality? That is, Why not section everyone? Essentially, the risk-averse obstetrician is sectioning everyone they can. But a risk-mitigator balances the risk of perinatal mortality with the risk of maternal mortality. Woman who undergo TOLAC, regardless of how they eventually deliver, have a maternal mortality rate of 3.8 per 100,000 compared to 13.4 per 100,000 for women who undergo repeat cesarean delivery.

The bottom line: if a hospital administrator and anesthetic provider will allow a primigravida to labor, then they should allow for a TOLAC, particularly as women turn instead to TOLACs at home. Even a less than optimal hospital setting (such as spotty anesthesia availability) provides a dramatically better outcome than a TOLAC at home. A risk-mitigator seeks absolute risk reduction and optimized outcomes, not shifting fault and responsibility to a different setting. If a patient has a uterine rupture at home because a hospital administrator took away her opportunity to labor in a hospital, then that hospital administrator (or physician) is still morally and perhaps legally responsible.

To mitigate risk, we must think about populations of patients, not individual patients. Good providers do not consider the risks of procedures and interventions for individual patients, they consider the risks for the total population. Again, this sounds counter-intuitive. But only when we observe the total population’s outcomes are we able to appreciate, for example, that mammography doesn’t decrease the risk of death from cancer (that is, death from all cancers). Or, in the current example, that offering a TOLAC in the hospital setting, even if that hospital setting is less than ideal, improves the overall outcomes of the population.

In general, the risk-averse thinking of many providers and risk management personnel is actually contributing to the worsening of outcomes in American obstetrics, particularly in relation to the maternal mortality rate. As cesarean deliveries are always (incorrectly) perceived to be the “better safe than sorry” solution, we have seen a sky-rocketing rate with an unnecessary and concomitant increase in maternal mortality.

If a risk-averse emergency room provider, always worried about lawsuits, orders an unnecessary CT scan, which then reveals an incidental finding, which then leads to an unnecessary surgery, which then results in a negative patient outcome, then risk-aversion has caused harm. Out of fear of a lawsuit, the provider has now caused a negative outcome and simultaneously increased cost to our healthcare system. Such over-diagnosis is rampant in the United States and it is often borne out of risk-aversion. The result, however, is worse outcomes at increased cost. The irony is, the more money we spend, the poorer our outcomes are, compared to other developed nations.

We are all risk-averse; that is, none of us normally want to take unnecessary risks. Yet every time we do surgery or prescribe a medicine, it should be because we are seeking to reduce total risk.

Humans don’t always make rational decisions. People smoke, even though they know it’s bad for them. If you choose to go skydiving, you are choosing to increase your risk of death but decide that the experience is worth it. When we operate on a woman who has a ruptured ectopic pregnancy, we are exposing our patient to a surgical risk of mortality; nevertheless, we do it because we are decreasing the greater risk of death from the ectopic pregnancy.

We must thoroughly understand both real risks and real benefits, both intended and unintended consequences, and both short-term and long-term effects. We cannot filter our counseling through emotional fear of Boogeymen. Every intervention has risks associated with it. Every year, a certain number of elderly men and women die sudden deaths after being prescribed Bactrim. In fact, among older patients taking Aldactone, 0.74% die after taking a single course Bactrim. That’s a real Boogeyman. How many doctors call-in a course of Bactrim over the phone for a possible UTI without knowing this fact or taking an appropriate history? And how many of those patients even have a UTI? Few doctors think that this prescription might kill the patient. Many people would do this routinely, exposing their patient to an almost 1% risk of death, but would never offer a TOLAC or an external cephalic version, both of which are far safer.

We don’t get brownie points for being risk-averse nor should we strive to be bold Cowboys. What we should do is fully understand risks and benefits of everything that we do, including the unintended consequences, and then, using risk-modeling, apply the safest path out of trouble to our patients. We have to clearly communicate risks and benefits in meaningful ways so that our patients can then make truly informed decisions based on their personal values.