I get frustrated daily with the misuse of science by both scientists and non-scientists. Every good social media argument has someone claiming “science” in a gotcha moment, usually not understanding what science even is. Every medical conference I attend is smattered with folks holding their coffee cups with both hands smattering about “data” while not understanding data.

Here are some helpful hints about science.

Science isn’t picking a published article in PubMed and touting its results. Here’s an axiom: For every published article in PubMed that purports to show some fact, there is at least one other article that purports to show the exact opposite fact. Any two people can both cite some study to support their diametrically opposed beliefs. A corollary of this axiom is that at least 50% of all published articles are false (we think it’s closer to 80%). It’s not even about picking the most recent article. Most literature, in time, will be refuted by other literature, but incorrect articles don’t get judiciously deleted from PubMed or the internet or from other articles and textbooks which reference them.

Example: Elderly people should take aspirin or the elderly should not take aspirin or even the most prestigious journals (Science and Nature) don’t always get it right.

Science isn’t believing what somebody says because they have an M.D. or a Ph.D. after their name. This is the logical fallacy called an appeal to authority. It’s true that if you have a question about your health that you are, on average, going to get better advice from a physician than a cab driver (no offense to cab drivers), but both are wrong quite often. People with doctoral degrees are just as entitled as the rest of the population to have incorrect beliefs, biases, etc. Some doctors are just downright con-artists and charlatans; many of those are frequently on TV or social media (perhaps because they can’t make money the regular way). Be careful when someone asks you to believe him just because he went to school.

Example: Board certification doesn’t necessarily equal good care or Dr. Oz is a liar.

Science isn’t believing something just because an apparent consensus of science says it’s true. Given enough time, the consensus of scientists is eventually wrong. It is definitely better to listen to a large group of scientists or physicians than one or two; but even then many groups of physicians or scientists disagree with one another, depending on what their special interests might be. Oftentimes, a consensus of opinion merely reflects the prevalent bias in a field (bandwagon fallacy) and the flawed belief might still emanate from only one study or one influential personality. Consensus is usually misrepresented by those who benefit from there being a consensus (think companies making money or academics making careers); this can be done casually (Most doctors agree that …)or formally.

Example: Superceded scientific theories or up to 50% of published guidelines are untrustworthy.

Science isn’t believing in things that make sense or that can be explained to you. The truth is, we are all more likely to believe in things that make sense to us than in things that don’t; if we can understand why or how something might work then we are more likely to believe it which also means we are more likely to cherry-pick and filter evidence in support of the belief (the confirmation bias). But science, especially biological science, usually studies complex systems. Complex systems are defined as complex because understanding the function and outcome of any given component of the system may not predict the function and outcome of the whole system (think HgA1c and macrovascular disease in diabetics or SSRIs and suicidality). That’s a fancy way of saying that complex systems probably won’t make sense to you in first-order terms. Often, real science asks us to accept things that the data supports without understanding how they work.

Example: Simpson’s paradox or dealing with nonintuitive findings.

Science isn’t citing random evidence for things that you already believe in. Most people I know who use PubMed or even conduct a scientific study do so seeking to prove what they already believe. This means that they design the search or study in a way much more likely to confirm their beliefs than to reject them. That’s not science. Science is about disproving your belief. Design your search or study in a way best suited to show that you are wrong. Internet arguers love to sprinkle their arguments with disjoined nuggets of evidence – anything they can find that agrees with them. That might seem like a good way to convince your opponent (it isn’t by the way), but it’s not science.

Example: The confirmation bias

Science isn’t fancy words or formulas. Unfortunately, many folks feel compelled to believe something just because it is written with sophisticated jargon or cites theorems or math. Sentence length and number of syllables in words don’t correlate with truthfulness; in fact, you should worry that someone might be attempting to pull one over on you if they go to great lengths to make something more complicated than it needs to be (keeping in mind that sometimes things need to be complicated).

Example: Fancy terms don’t equal science.

Science isn’t a P-value less than 0.05. This one gets me more than anything. Scientific studies are about rigorous statistical interpretation but most people think that means using some tool to find a P-value < 0.05 or performing an ANOVA analysis; it does not. I call this the naive interpretation of statistics. Again, remember that any given article (with a significant P-value) has an opposite article (that also has a significant P-value). Apart from the fact that P-values can easily be hacked and any statistician worth her salt can organize data in a way to show an odds ratio ranging from 0.1 to 10 (true story!), we must consider the non-naive view of statistics which involves determining the pre-study likelihood of the proposed hypothesis and placing the study in that context (Bayesian updating). A corollary of this, then, is that the published literature must be taken and analyzed in total for any given question. Want to know if vaccines cause autism (they don’t): you have 26,000 studies to consider.

Example: P-hacking for novices or why most published research is wrong.

Science is not something that can be invoked; that is, it is not a god. When someone invokes “science” to make a point, I have learned to stop listening; that is a sure tell that they either don’t know what they are talking about, don’t have any evidence, or both. That is called scientism, not science.

So what is science?

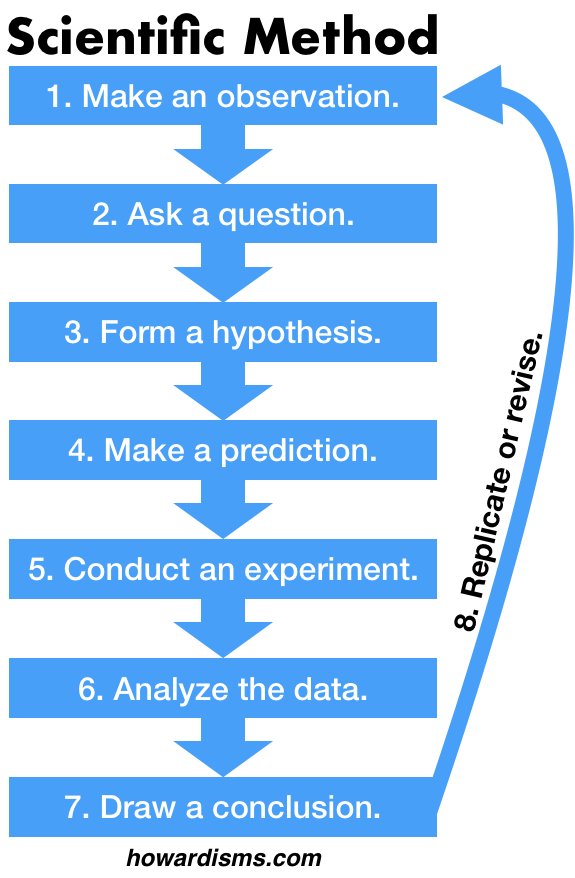

Science is about replication. Findings that are replicated over time are much more likely to be true than those that appear in one-off studies or in mixed, heterogeneous data or collection of studies. One study sometimes is enough to change our practice or our beliefs, but it usually isn’t, especially when it contradicts prior pieces of evidence.

Science is about uncertainty. Some people who claim to like science love collecting little facts and storing them away as truths; but science is about measuring degrees of certainty and uncertainty. The truth is we don’t know or aren’t sure about most things, particularly in the biological sciences.

Science is about seeking to disprove things. I’ll say here that there are other ways of doing science and I don’t want to get into epistemology or the philosophy of science just now; but, our current scientific methods are predicated upon disproving ideas. Our data tools are designed for this purpose. This means, practically, that you should seek to discredit and disprove ideas both in search and experiment; those ideas that survive such vigorous assaults can live to fight another day.

Science is about being skeptical. The last point leads to this one. Scientism blindly accepts neatly packaged “facts;” science questions them. A healthy skepticism is necessary. Bad science and bad medicine are just as likely to come from Harvard and Yale as from Dr. Mercola and Dr. Oz. Look for the evidence for and against all of your beliefs.

Science is about change. History tells us this axiom if nothing else. I dare everyone to go back 30 years ago and collect the things science told them were “true” about their area of interest and compare them to our current beliefs. If science didn’t change, we would still be letting blood with leeches. We must embrace change and we must integrate new evidence into our practice. Most people realize this on some level; they are quick to make fun of the false and sometimes comical beliefs of prior generations. Unfortunately, the current generation always believes that they are not susceptible to the mistakes, or at least the rate of mistakes, that prior generations were. This is simply not true (it’s called the optimism bias and it’s far-reaching). We are still equally wrong – wrong about different things, perhaps, but still wrong about the same amounts of things. And the change comes fast while old articles and old information on the Internet seems to persist forever.

<end rant>