Unfortunately, I’ve recently seen a rash of patients who have been told by other gynecologists that they suffer from a significant congenital uterine malformation that will require extensive workup, probable surgery, and will significantly hinder their ability to reproduce. Yet, in each case, the women either had no uterine abnormality at all or a mild arcuate appearance of the uterus – despite being informed that they had a didelphic or deep septate uterus. What I’ve noticed in each case is that the original gynecologist didn’t understand the basic nomenclature used to describe Müllerian anomalies and they certainly did not understand how to interpret the ultrasound findings correctly, since in each case the women were to be referred for an MRI as a first step in additional evaluation. The wasted cost and mental anguish expended upon these patients was completely unnecessary. So here are four tips for correctly diagnosing uterine anomalies with ultrasound to try to prevent these common mistakes.

1. Know the embryology and nomenclature well.

People hate to think about embryology, but understanding the embryology of the uterus is essential to correctly understanding the different types of uterine anomalies and how to diagnose them. Too often, physicians will refer to any uterine anomaly with a broad term like bicornuate uterus due to a lack of understanding of the terminology. So let’s have a brief review.

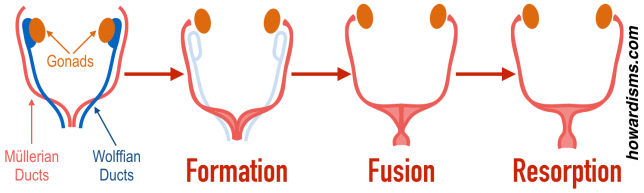

The uterus, fallopian tubes, and the upper two-thirds of the vagina arise from the bilateral Müllerian ducts (or paramesonephric ducts) after sexual differentiation and regression of the Wolffian ducts. Problems may arise from the failure of either or both ducts to form or form completely. The lower third of the vagina develops from the ascending sinovaginal bulb, which must eventually fuse with the developed Müllerian system.

These structures must all completely form, fuse together, and, finally, the horizontal and vertical septa created during fusion must resorb to have normal female anatomy.

Therefore, abnormalities may develop from a lack of development (agenesis or hypoplasia), a problem with fusion, or a problem with septal resorption.

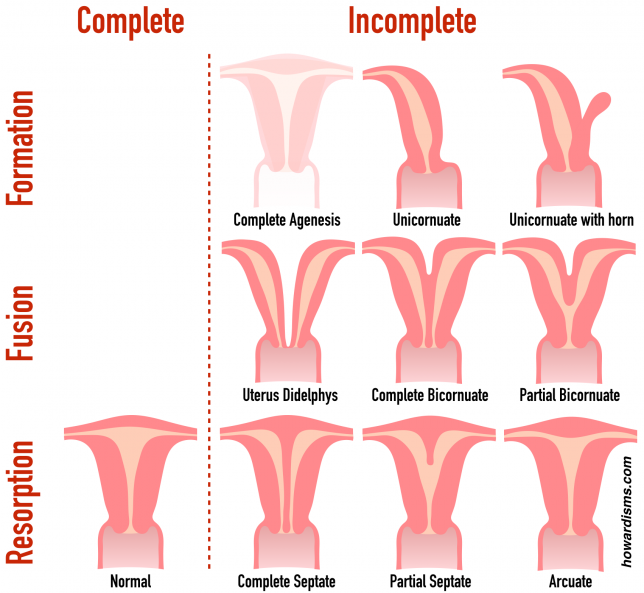

- If neither Müllerian duct forms, then complete Müllerian agenesis will occur (no uterus, no tubes, no cervix, and no upper portion of the vagina).

- If only one of the bilateral Müllerian ducts form, then a unicornuate uterus will result. Sometimes, there is partial development of one side, which can result in a rudimentary horn which may or may not communicate with the completely developed side.

- Partial formation or hypoplasia of either or both Müllerian ducts may occur, resulting in things like missing tubes, a missing cervix, a missing fundus, a missing endometrium, a missing upper vagina, or any combination of these structures missing or incompletely formed on one or both sides.

- Incomplete fusion of the formed ducts will result in a didelphic uterus, with partial fusion resulting in a bicornuate uterus.

- A lack of resorption of the vertical septum will result in a complete or partial septate uterus.

- A lack of total resorption of the vertical septum can result in an arcuate uterus.

2. Define the external contour of the fundus.

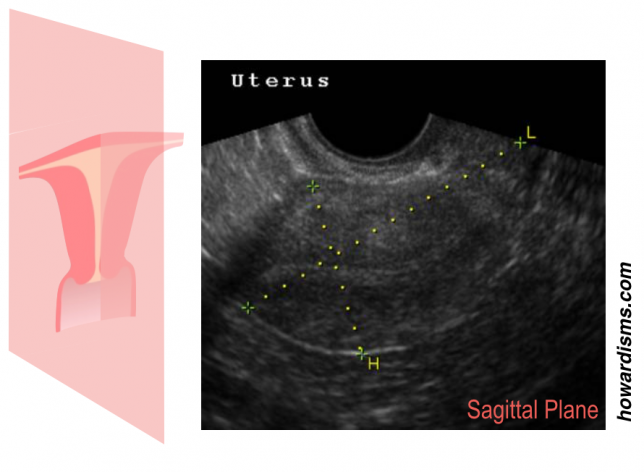

When any woman has an ultrasound of the uterus, always scan completely through the sagittal view of the uterus, following the contour of the fundus, to see if there is an abnormality.

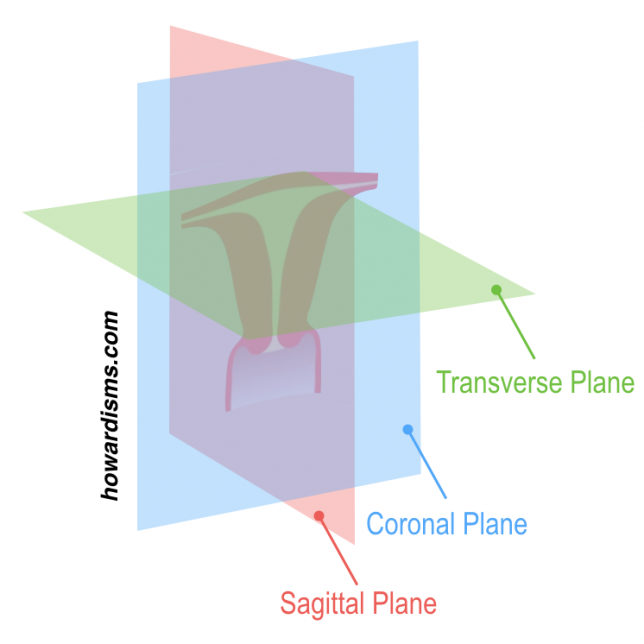

Recall the anatomic planes:

This means that the sagittal plane of the uterus looks like this:

By scanning from one cornua to the other and watching the top of the uterus, abnormalities related to incomplete fusion (like a bicornuate or uterine didelphys) can be detected. This view is always easy to obtain with transvaginal ultrasound.

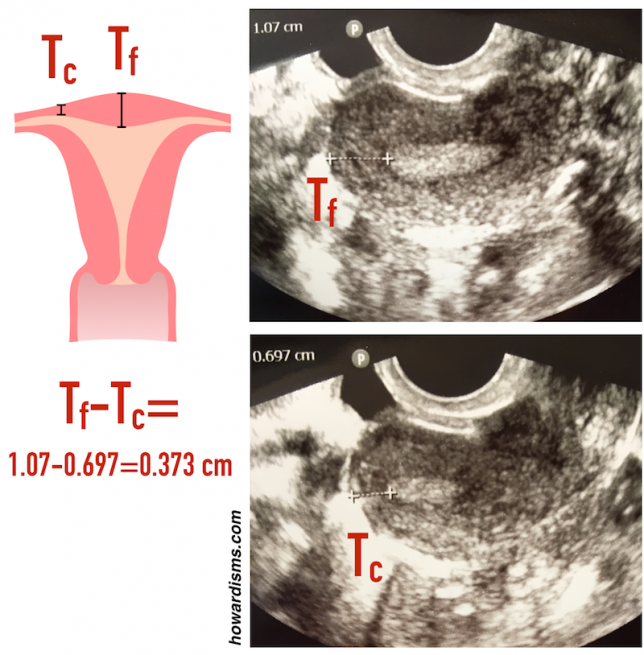

3. Compare the fundal myometrial thickness to the corneal myometrial thickness.

While looking at the external contour of the uterus, also note the thickness of the fundal myometrium in two places: near the cornua and in the center of the fundus. If there is a concern about an abnormality, then the thickness of the myometrium can be measured near the cornua (Tc) and also measured at the center of the fundus, at its thickest point (Tf). The difference in these two measurements (Tf-Tc) approximates the size of internal indentation of the uterine cavity which might represent an arcuate or septate uterus.

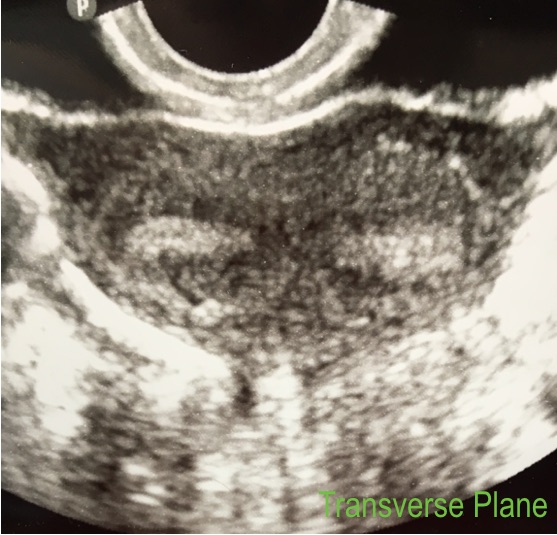

In this case, the difference is 3.7 mm, which is not clinically significant but can make the uterus look concerning when the endometrium is viewed in a transverse plane:

The endometrium is divided by the small internal indentation of the myometrium, giving a “cat’s eyes” sign. This patient was told that she had a Müllerian abnormality (a septate uterus) based on this ultrasound view and was told she would likely need surgery to correct it. Yet, the same conventional ultrasound, in a universally obtainable sagittal plane, shows only a 3.7 mm indentation, which doesn’t even qualify it as arcuate by modern criteria. Many thought-leaders are moving to remove the classification of arcuate uterus from the nomenclature entirely since this common finding has little to no impact on reproduction.

Müllerian abnormalities can affect fertility in two primary ways: an increased risk of miscarriage and/or an increased risk of preterm birth. Miscarriage risk is increased in cases where some of the surface area of the uterine cavity is replaced with septal tissue, which is less vascular and therefore less able to sustain an implanted pregnancy than normal myometrial tissue. Therefore, uterine anomalies due to incomplete resorption are associated with an increased risk of miscarriage.

Preterm birth is increased if the size of the cavity of the uterus is diminished or constricted. Uterine hypoplasia or unicornuate, bicornuate, or didelphic uteri are all associated with a physically smaller cavity and therefore an increased risk of preterm birth.

A uterus with both diminished cavity size and an increased avascular surface area, such a complete septate uterus, would increase the risk of both miscarriage and preterm labor. Fortunately, septate uteri are often candidates for septoplasty and this surgery can improve pregnancy outcomes.

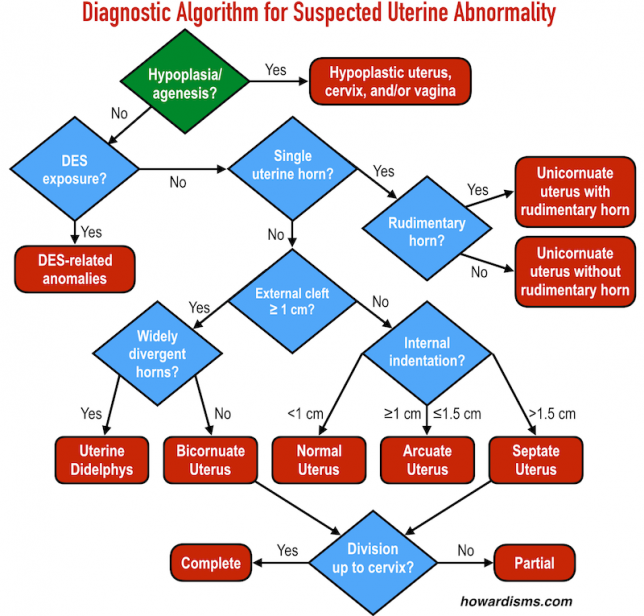

The following algorithm can be implemented with conventional transvaginal ultrasound in most patients, simply by examining the external contour of the uterus (looking for a cleft) and assessing the internal cavity as described above:

4. Use saline infusion, 3D ultrasound.

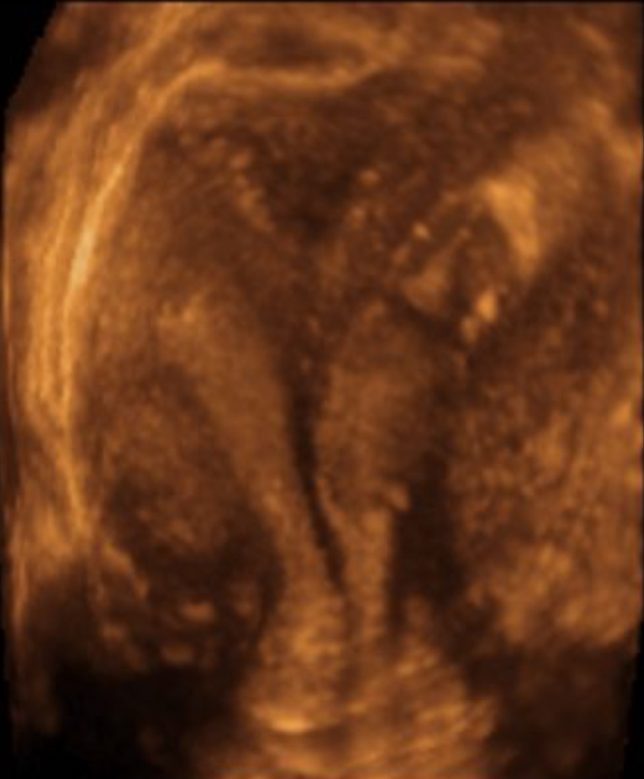

In some cases, traditional 2D ultrasound is insufficient to definitively determine the nature of the uterine malformation. It is usually very difficult to get a true coronal view of the uterus, which would be most helpful for assessing a deep septum or a deep cleft. If there is a suspected cleft or a deep septum, then 3D ultrasound, with or without saline infusion, can be diagnostic, and is less expensive and more accessible than MRI.

Here is a coronal view of a complete septate uterus reconstructed using 3D ultrasound:

Note that there is no cleft along the top of the fundus, indicating complete fusion, but a septum that extends all the way through the cervix, indicating a complete lack of resorption. The addition of saline infusion can further enhance this type of study.

MRI may still be necessary to discover a rudimentary horn or other unusual anomalies, but these are not usually clinically relevant and often don’t inform the counseling of women regarding their reproductive options and outcomes.

What else?

Don’t scare patients with misinformation. There just is no clinical relevance to mild fundal indentations or even arcuate uteri. These are essentially normal variants.

Examine the vagina well. A careful exam of the vagina and cervix may reveal vaginal septa or other abnormalities. It’s amazing how often women go many years not knowing that they have a vaginal septum or even two cervices!

Check out my video on Müllerian abnormalities for more information: