The annual Well-Woman Visit is in need of re-invigoration and redefinition. Unfortunately, in many physicians’ practices and in the minds of many millions of patients, the annual visit is almost solely defined by the Pap smear. For many women, the only reason they even go to the gynecologist yearly is for birth control or because they believe that they need a pap smear. When they receive a normal pap smear result letter in the mail, they have the impression that all is well regarding their female health. Add to this a mammogram later in life, perhaps a pelvic exam, and then some non-evidence-based standard counseling (like calcium supplementation), and, voila!, you have the annual visit for most women in the US.

What is a woman to think when she learns in the media that a pap smear isn’t necessary every year? Or that long-acting reversible contraception lasts 3-5 years and is much more effective than the pills they are taking? Or that mammograms may not be necessary until age 45 or 50, and, even then, perhaps needed only every two years? Or that yearly pelvic exams and breast exams may not be beneficial? What value does the patient then see in a yearly visit with her gynecologist? Often they see no value. But this isn’t the media’s fault, it’s the physicians’ fault for not adding that value to the visit. A generation of “I’ll see you next year for your pap smear” has been sending the wrong message to patients.

So what is the value of the Annual Visit? To understand the answer, we need to understand the problems that confront our patients, and what interventions we have available to address those problems. We also need to understand the effectiveness of the interventions in our arsenal. Cervical cancer is not our patients’ number one problem and should not be our sole focus.

3,939 women in the United States died from cervical cancer in 2010, while nearly 8,700 committed suicide in the same year. Yet, while millions of women have unnecessary pap tests each year, those same women often receive no intervention or screening for mood disorders, substance abuse disorders, or other predictors of suicidal ideation.

Here are the leading causes of death for women we should consider: substance abuse, accidents, suicide, cancers (in order: breast, lung, colorectal, uterine, ovarian, melanoma, non-Hodgkins lymphoma, brain, renal), heart disease, diabetes, sexually transmitted infections (including HIV), influenza and pneumonia.

We should also consider things that affect quality of life and other social determinants of health, such as preventing unintended pregnancy and treating mood disorders, substance abuse, and tobacco abuse.

We need to focus on screening for modifiable risk factors and diseases that lead to improved quality of life and preventing unnecessary death. Let’s look at some specifics.

History should screen for:

- Tobacco, alcohol, and illicit drug use

- Intimate partner violence

- Depression and other mood disorders

- Eating disorders

- Risk factors for heart disease and diabetes

- Family history of modifiable genetic predispositions, such as a history of breast and/or ovarian cancer, colon cancer, heart disease, diabetes, etc.

Counseling should be provided for anything discovered above, and also for:

- Family planning

- Emphasis should be on Tier 1 birth control: IUD’s, implants, sterilization

- Encourage women of reproductive age who are capable of becoming pregnant to use folic acid

- Diet/exercise/activity

- Women 55-79 should take a daily baby aspirin for stroke prevention if benefit outweighs risk, calculated here.

Cancer Screenings:

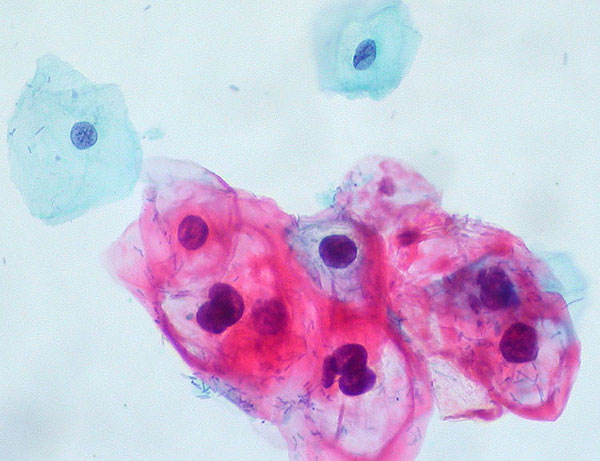

- Cervical: first Pap smear at age 21, followed by one every three years until age 30. After age 30, she should receive a Pap smear every three years, or the Pap smear plus HPV co-testing every five years. This goes on until age 65, assuming there are no abnormalities.

- Breast: for the average risk woman, there are three contradictory guidelines currently available:

- annual mammography should start at age 40 and continue yearly (ACOG), or

- start at age 45 and occur yearly until age 55, then every other year (ACS), or

- start at age 50 and occur every other year until age 75 (USPTFS).

- Ovarian: routine screening is, in theory, a pelvic exam; in practice, this has not been shown to be effective and may be harmful. Screening with transvaginal ultrasound and/or CA-125 also is not recommended. A more effective strategy may be a review of systems focusing on new-onset pelvic symptoms such as bloating, discomfort, etc.

- Colorectal: women between the ages of 50-75 should have either:

- colonoscopy every ten years (preferable), or

- annual fecal occult blood testing, or

- sigmoidoscopy every five years with fecal occult blood testing every three years.

Other Screenings:

- All sexually active women under age 25 should be screened for chlamydia

- High risk women should be screened for chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, HIV

- Yearly HIV screening may be appropriative depending upon the incidence in your area

- Women over 45 should having lipid screening every five years (and younger women if at increased risk)

- Evaluate BMI, Blood Pressure yearly

- Screening for diabetes at age 45 and every 3 years (earlier and more often if risk factors)

- DEXA Screening for women after 65 and then every 2-3 years (earlier depending on risk factors)

Immunizations:

- Current immunizations schedules are available here.

- Don’t forget about Gardasil!

An excellent summary of the yearly female exam, with more detail than is provided here, is available from the American Academy of Family Physicians here.

Another resource that compares the evidence-basis of various recommendations is available here.