Good clinical thinking is good critical thinking. Critical thinking in medicine requires a variety of tools in our cognitive armamentarium. We must be aware of our biases. We must understand what constitutes good evidence and bad evidence. But perhaps the most important characteristic of a good critical thinker is a large dose of healthy skepticism.

A good scientist is always questioning how things work, why they work, etc. A scientific skeptic goes just one step beyond and questions if things work at all; a scientific skeptic questions the most fundamental scientific dogmas and demands a certain level of evidence before determining whether an idea is science or pseudoscience.

The average, good scientist, for example, holds that the constancy of the speed of light is an immutable truth in the universe. The great scientist, the skeptical scientist, on the other hand, is not bothered by challenging this assumption and seeing where it goes (and today there are many variable speed of light theories). Neither of these theories are pseudoscience. Neither are proven. Neither should be held out as dogma based on our current level of evidence. Both have their place in a healthy scientific debate.

But there are “theories” which are pseudoscience. For example, the flat-earth theory today can only be regarded as pseudoscience, though it once was accepted by large portions of the scientific community (in ancient Mesopotamia). Yet some skeptic (in ancient Greece) challenged the dogma and eventually this false idea was displaced. Today, the flat-earth theory should not be held out with equal footing with the spherical earth model. Students should not be presented the evidence for both and then allowed to decide for themselves (as one might do for constant versus variable speed of light theories).

The skeptic is comfortable, after an inquisitive process, labelling something as science or as pseudoscience. In medicine, a common pseudoscientific concept is homeopathy. It wasn’t always. Two hundred years ago, we still believed in things like the four humors of the body, counter-irritation, blood-letting, and we hadn’t yet discovered the germ theory of disease. In this environment, homeopathy held equal status. But today, it should be relegated to the dustbin of history. The problem is, though, homeopathy is more popular than ever. Homeopathic products are available for purchase at nearly every pharmacy. Popular medical websites list homeopathic treatments for common ailments as if they were authentic treatments. Doctors are seemingly afraid to speak ill of these and other pseudoscientific claims (e.g., reflexology, chelation therapy, etc) for fear of alienating their patients or because they simply don’t know better. Worse, many doctors even advocate for these practices.

Imagine going to a science class in school. The teacher tells the class that the earth is round. Little Johnny raises his hand and tells the teacher that he heard that the earth was flat. The teacher tells the class, “Yes that is another possibility and a lot of people throughout history have believed that. There is a lot of evidence over thousands of years to support that idea. Both round and flat earths are fine as long as we make up our own minds about which model best suites us individually.” Surely, any responsible parent would call the school Superintendent that afternoon. Yet many of those same parents actually seek out physicians who embrace pseudoscience in their practices. It is no exaggeration to say that there is just as much scientific evidence to support a flat earth as there is homeopathy. Why the difference in perception then?

Mainly because physicians, by and large, do not act like scientists, they don’t think like scientists, and they don’t represent themselves as scientists to their patients. What’s more, there are billions of dollars to be made in hocking homeopathy and dozens of other unscientific products to unsuspecting and uneducated consumers. No one today is making any money off of the flat earth theory, except maybe the feckless folks at the Flat Earth Society. These pseudoscientific ideas are marketed with anecdote and testimonials or poorly designed and often rigged studies; but mainstream medical science is often no better, still being manipulated by companies who need to make money or academics who need to make reputations.

The point: A great physician is a great skeptic. We should routinely question our assumptions. How many dogmas would exist today in medicine if we didn’t dare question the status quo? Bloodletting, humorism, Mesmerism, Hijama, trepanning, etc. have all been displaced because a skeptic dared question whether these practices were effective. Many innovators or questioners of dogma were ostracized for their work, like Ignaz Semmelweis, who was fired for daring to suggest that we should wash our hands before doing pelvic exams on women in labor (even though he was able to demonstrate an amazing decline in death from puerperal fever). In retrospect, Semmelweis hit upon one of the most important discoveries in medical history. Yet, at the time, he was ridiculed because he challenged the status quo. Had his peers held him to science-based scrutiny, he would have been praised while he was still alive.

Scientists, and physicians as scientists, must maintain an atmosphere that welcomes challenging the traditional view. When a new finding is published in a journal, the community of physician-scientists must greet it with a skeptical mindset. Today, most physicians view a new published finding with total acceptance. They assume that folks smarter than themselves shepherded the study through publication and that a bad study or a false conclusion couldn’t make it all the way to their mailbox or inbox. Yet, our biological science journals are filled with incompetent peer review, poor statistical methodologies, publication bias, false positive and false negative findings, and, in some cases, outright academic fraud. The majority of published findings are either false or insignificant. Each new publication, then, should be met with a skeptical view and the physician-scientist must be adept at critically appraising literature.

Of course, the extreme implementation of this skeptical view is to trust no new finding and to just continue bleeding patients to balance the four humors. The Bayesian worldview helps balance these two extremes. When something is statistically more likely to be true than false, then the Bayesian thinker accepts it as tentatively true but doesn’t become dogmatic about it, realizing that the situation may change with new evidence.

Indeed, we should always be welcoming new evidence. This is fundamental to critical thinking. If you believe a thing to be true, try to disprove it. Honestly try. If you cannot, try again next year. As long as you cannot disprove it, then use it. But approach each “fact” with skepticism.

The tendency to accept every new thing that comes down the pike has given us things like thalidomide and DES. Thalidomide was brought to market in 1956 and was used in pregnant women for treatment of nausea without any human safety studies. More than 10,000 children were born with serious birth defects and more than 2,000 died before the drug was finally taken off the market in 1961. The companies that marketed the drug around the world had declared it safe during pregnancy even though no such data existed. And doctors were more than willing to recommend it to thousands of pregnant women without asking critical questions, like, Does it work? Or, Is it safe? Unfortunately, today, most physicians still receive most of their education about drugs from the companies that market them. Thalidomide was withdrawn from the market not because doctors were outraged after observing birth defects in the babies they were delivering but because of public outcry. The doctors were happy to keep using the drug.

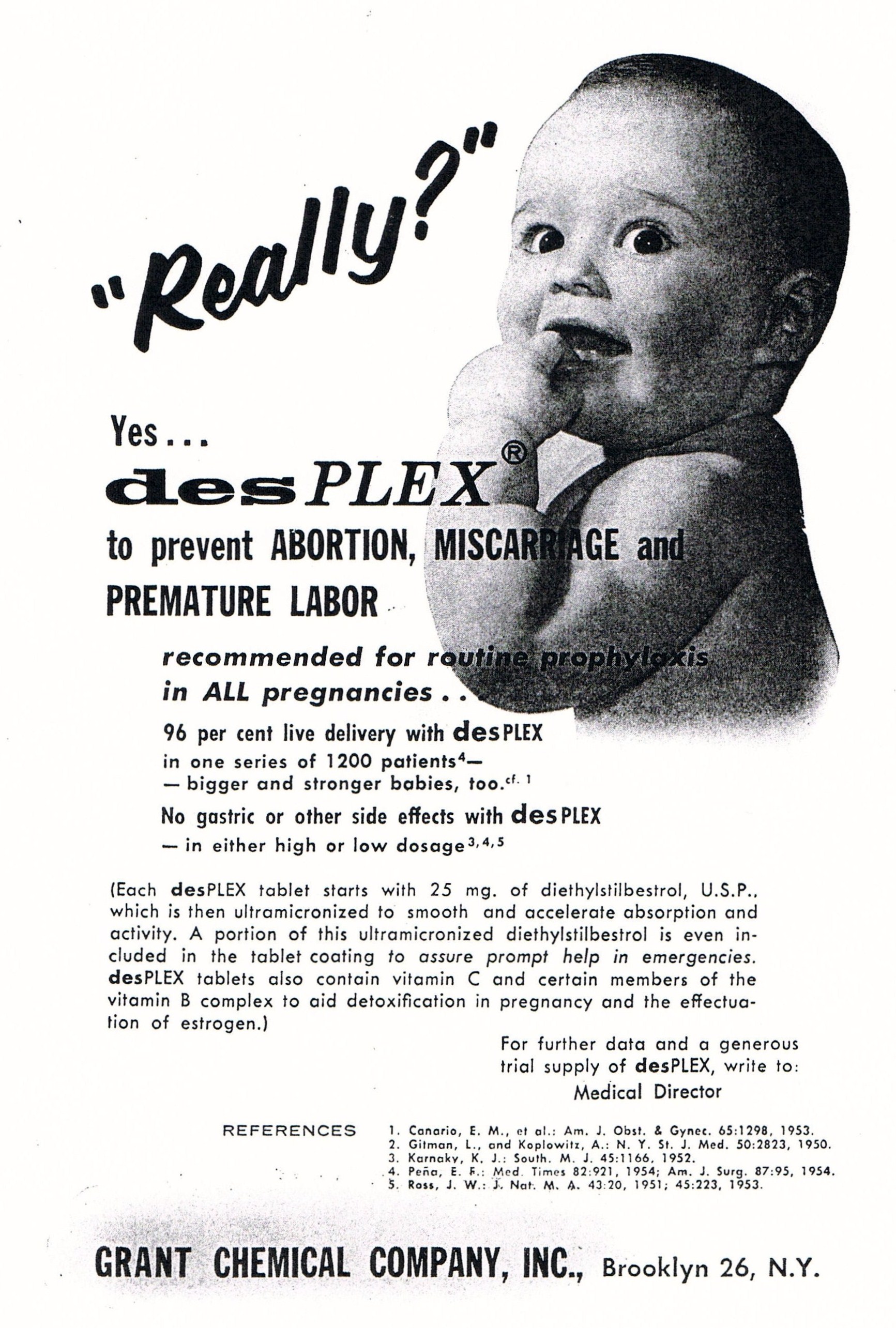

From 1940-1971, Diethylstilbestrol, or DES, was given to pregnant women to prevent miscarriages. In 1971, a report in the New England Journal of Medicine linked DES to clear cell adenocarcinoma of the vagina in the children of the women who had taken DES while pregnant. It took several more years for doctors to finally stop using the drug and off-label uses as an emergency contraceptive and to suppress lactation continued for nearly a decade. Like thalidomide, no safety studies confirmed that the drug was safe to use during pregnancy. But unlike thalidomide, doctors knew early on that DES didn’t work. In fact, in 1953, in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Dieckmann et al. published a double-blinded clinical trial from the University of Chicago which showed that DES had no effect on the miscarriage rate. There had never been any data that showed that it worked. Yet doctors embraced it as an acceptable therapy based on anecdote and marketing and despite a lack of efficacy or safety data. Then, even after a large, well-designed study showed that it didn’t work, doctors continued to prescribe it for another 20 years, exposing almost 2 million women to the drug. First, do no harm. Each doctor who prescribed the drug after 1953 violated medical ethics in doing so. (Note that the advertisement above comes from after 1953)

If this sounds strange that doctors would ignore such clear-cut scientific evidence, it isn’t. Today, doctors routinely still prescribe progesterone supplementation for prevention of recurrent miscarriage, despite a lack of data to show efficacy. A study published in the New England Journal of Medicine in November of 2015 showed definitively that progesterone supplementation doesn’t benefit women who have suffered previous miscarriages. But this wasn’t new. This was what the consensus of literature had shown for nearly thirty years. There never was a quality study that said that we should be using progesterone for recurrent pregnancy loss, and reviews of the literature have consistently held that evidence was lacking. The author of this recent NEJM study stated in interviews that he doubted his study would change what doctors do. He’s right. That really is the point and it demonstrates the lost lesson of DES. Both DES and progesterone have no known benefit in preventing miscarriage; so don’t use them. The issue of birth defects is secondary. Again, just two critical questions, guided by sound medical ethics, would have prevented these situations: Does it work, and, Is it safe?

Good critical thinking is really not that hard.

A good critical thinker is curious about things. Ask simple and basic questions that can be subjected to evidence. Use PubMed or other databases to actively look for answers to simple questions, like, Does lysine prevent or treat oral herpetic lesions?

A good critical thinker is skeptical. If you find a small study, whose authors worked for a company that sells lysine, then be skeptical and keep digging.

A good critical thinker is humble. If you are currently recommending lysine to treat oral herpes, and you find that the Cochrane Database says that this practice is ineffective (it does), then stop telling patients to use the product. It’s nothing personal. Change or update your beliefs when presented with new data. Don’t keep using an intervention that doesn’t work for three decades after the science says it doesn’t work.