I hear an awful lot about swinging pendulums. As medicine, politics, or almost anything goes from one extreme to the other, we are told that this is explained and anticipated by some swinging pendulum, going from one viewpoint to the opposite extreme. If you wait, long enough, it will just swing back the other way.

But this is a bad metaphor. The behavior of a pendulum is governed by precise laws of physics. The contradictory trends in medicine, the stock market, politics, etc. are governed not by scientific laws but by human reaction and overreaction, by raw emotion and bias. The “truth” usually is in the middle of the extremes, but why can’t we just find the truth without venturing off on dangerous excursions? We can, if we use science correctly.

Take water, for example. Too little, you’ll die; too much, you’ll die. Things like water aren’t inherently good or bad, nor are most other things, like breastfeeding, cesarean delivery, mercury, vaccines, fertilizers, carbon-based energy, sugar, immigrants, guns, mosquitoes, or sex. All things are useful and necessary in the right amounts and harmful in the wrong amounts.

Lesson #1: Too much of a good thing and too little of a bad thing can both kill you.

Unfortunately, people are reactionary and make emotional decisions. If a cesarean delivery has the ability to save the lives of some mothers and babies, it must be a good thing (and vaginal delivery must be a bad thing); therefore, the more women who are delivered by cesarean, the better! This is an emotional reaction which has its basis in the truth that some women and babies do have their lives saved by cesarean, but the emotional extreme is fueled by a negative experience with perhaps a particular vaginal delivery, and it is augmented by the false idea that you can’t get too much of a good thing.

Women who personally have suffered an unnecessary cesarean delivery or who have seen someone else suffer from one, especially if a complication occurred, often will emotionally react in the opposite way: that all (or almost all) cesareans are unnecessary and avoidable. Thus, the pendulum swings from one emotional overreaction to another. Like water, there are few things that possess the ability to save a life as much as cesarean delivery, and also few things as dangerous. We have to use cesareans in the right amounts on the right patients, just like we have to drink the right amount of water.

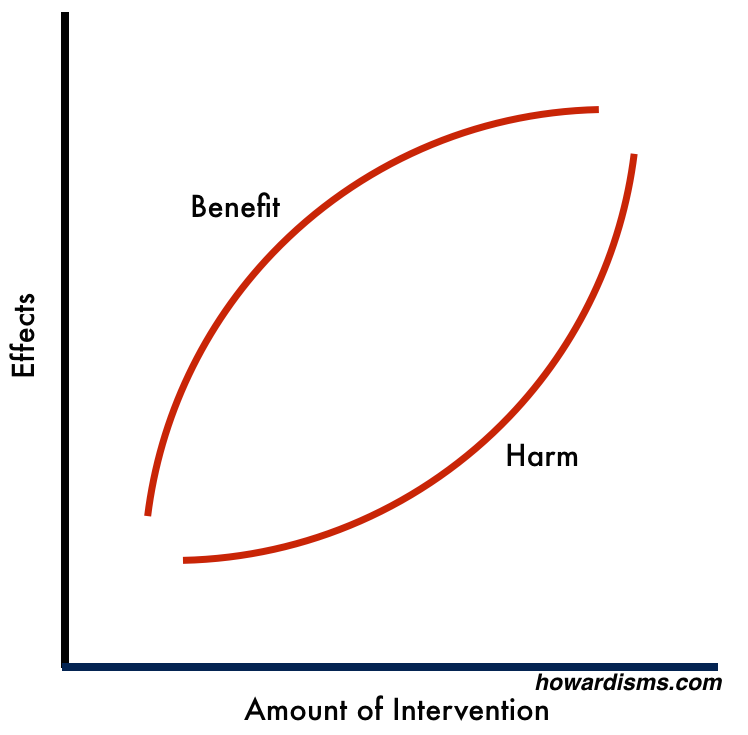

Here’s a chart of some obstetric interventions that cause harm when both under-utilized and when over-utilized:

Imagine the story for each of these interventions. Depending on your perspective, each intervention is either a good thing or a bad thing. This “good and bad” fallacy then leads to the next fallacy: that we don’t want any bad things at all, or, if it’s a good thing, we want as much goodness as possible. But these things aren’t inherently good or bad, better or worse; they are just things. They are made good or bad by how we use them. How we use them is a product of who we use them on and how often we use them.

In both cases, the extremes lead to more maternal and neonatal harm. So we have to focus on appropriate utilization.

Lesson #2: Everything we do in medicine has both risks and benefits.

Far too often, we focus only on the benefit of a given intervention. In some cases, we focus too much on the risk of an intervention (I think patients are more likely to do this than doctors). Again, the problem is focusing on one extreme or another. Everything we do has risks and benefits. Everything. The art of clinical medicine is finding a balance of risk and benefit for a given patient that satisfies her individual needs and desires. To do this well, we need to have a detailed understanding of the real benefits (including the magnitude of effect for each purported benefit), a real understanding of the risks (including unintended consequences), and an understanding of the patient’s priorities, needs, and objectives.

What are the risks of the MMR vaccine? 1 in 6 children get a fever; 1 in 20 get a mild rash; 1 in 75 get swelling in the lymph nodes; 1 in 3,000 have a seizure related to fever; 1 in 30,000 develop transient thrombocytopenia; 1 in 1 million develop a serious allergic reaction, with even fewer reporting deafness, coma, or brain damage.

What are the benefits of the MMR vaccine? The virtual elimination of measles, mumps, and rubella. From 1963-1983, it is estimated that the vaccine prevented 52 million cases of measles in the US, along with preventing 17,400 cases of intellectual disability, and 5,200 deaths. Prior to the introduction of the mumps vaccine, there were about 150,000 cases each year, many leading to sterilization of young boys; since the introduction of the vaccine, only about 265 cases are reported each year (mostly in unvaccinated children). Prior to the vaccine, rubella caused countless cases of congenital rubella syndrome in pregnant women; over a 100,000 cases still occur worldwide in unvaccinated areas of the world, but the condition has been eliminated in the US.

So should your patient (or her child) get the MMR vaccine? Yes. Why? The benefits far outweigh the risks.

Extremists on both sides don’t balance these scales in a way that leads to a good decision. Some emphasize risks while ignoring benefits, while others exaggerate benefits while ignoring risks. This leads to positions that over-utilize or under-utilize the intervention. How do we over-utilize MMR, you ask? Well, by giving it to pregnant women or those who suffer from a platelet abnormality, for example; someone might do this if they too much believe in its safety.

Some extremist philosophies increase the chance that the measure of either risk or benefit will be distorted. For example, many folks believe that if something is “natural” (whatever that means) it has no risks, while conversely something that is “unnatural” is nothing but risk. Such a person would never use fluoxetine (Prozac) to treat depression, but wouldn’t think twice about consuming large amounts of a solution containing hexatriacontane, n-hexadecanoic acid, cis-en-in-dicycloether, chamazulene, alpha-bisabolol oxide B, beta-eudesmol, spathulenol, p-cineme, n-decanoic acid, and nearly a hundred other chemicals (chamomile tea). Obviously, such analysis is not scientific but emotional.

So accept that everything has both risks and benefits. Saw palmetto has caused ventricular rupture and death while acetaminophen has cause liver failure and death in some patients. A cesarean raises the risk of maternal death by up to 8-fold compared to a vaginal delivery, but, in some cases, it might decrease an individual woman’s risk of death, given the clinical circumstances.

Lesson #3: A good doctor fairly weighs risks and benefits for the patient in front of her.

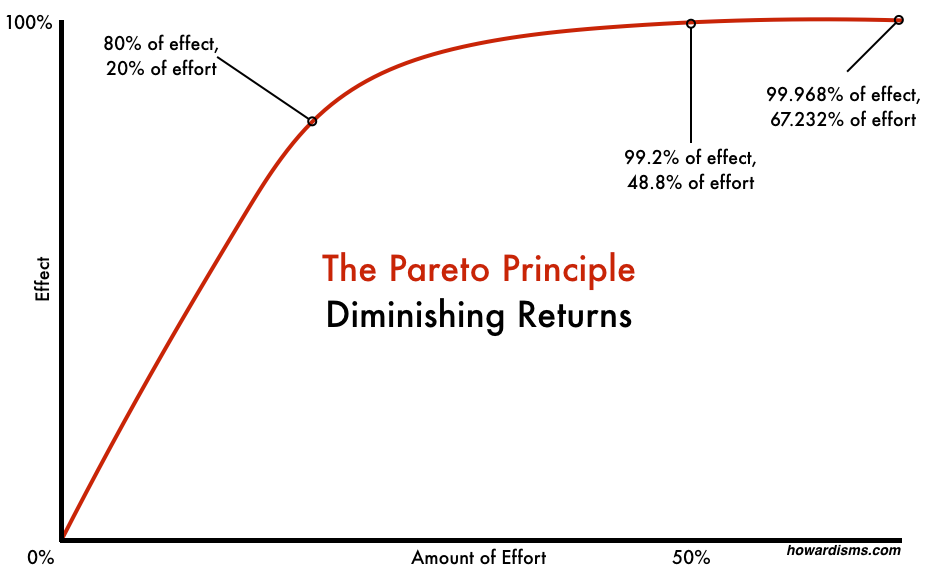

In general, as an intervention becomes more utilized, less benefit will be returned for each additional use. At the same time, more harm will be accrued for each additional use. Think of this like the law of diminishing returns or the Pareto principle. The Pareto principle states that roughly 80% of effect is seen from 20% of effort. Of the true benefit that comes from cesarean delivery, 80% of it will be gained by just 20% of women who have cesareans. At the same time, 80% of the harm that results from cesarean delivery will fall upon just 20% of patients.

The Pareto principle holds true across many scientific and sociological disciplines. Why is it true for medical interventions? One reason is the way medical studies are designed. Due to selection criteria, often the best (healthiest) candidates for an intervention are selected, while at the same time those who would tend to benefit the most from an intervention are selected. So for example, a study of cesarean delivery that would show the most benefit with the least harm might be a study that compares maternal and neonatal outcome among healthy, non-obese women (the healthiest patients) who have Category 3 fetal tracings (the worst fetuses), randomized to emergent cesarean delivery or expectant management. This “low hanging fruit” provides the most bang for the buck (the most benefit for the risk).

But then, in clinical practice, diagnostic and therapeutic drift start to occur. The return on investment (amount of benefit received for risk expended) will start to diminish when we now apply the intervention (cesarean delivery) to a patient population of obese women who smoke (who will have worse surgical outcomes) and whose fetuses only have Category 2 fetal tracings (meaning that they are almost all healthy). Just a little bit of drift is necessary to move from one similar but importantly different patient type to another and completely flip the scales from benefit to harm.

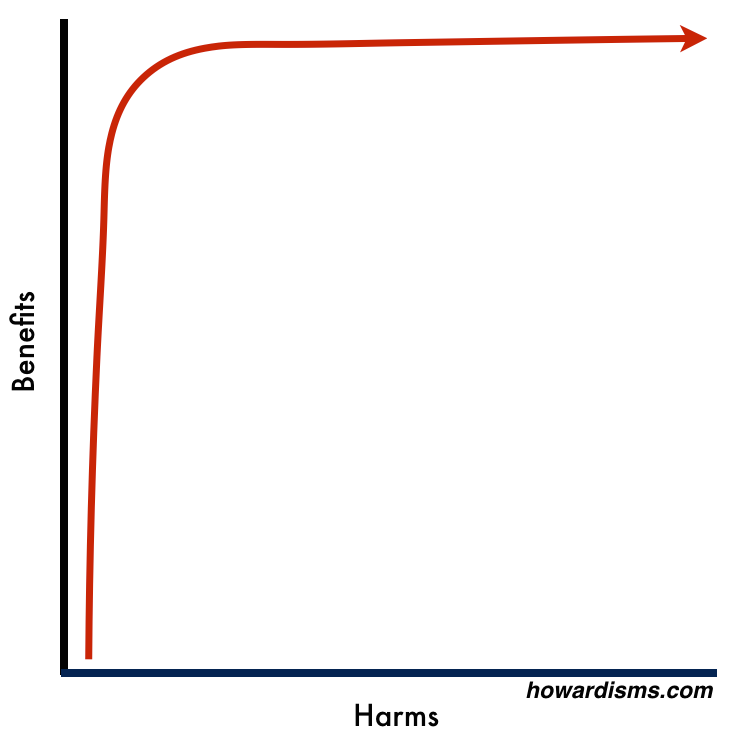

Another way of visualizing this is with the graph below:

As the red line moves up the left side of the graph, we are catching all the low hanging fruit: those who will most benefit from the intervention who also have the least to risk. Most clinical studies are conducted on patient populations who live in the lower half of the graph (and this is why the expected positive effect of many interventions are often not seen in practice).

Eventually, the graph makes a hard right-hand turn: Patients are still gaining marginal amounts of benefit, but at a cost of harm that is far too great to justify the benefit. A clinical trial conducted on this part of the graph would rarely lead to adoption of the intervention into clinical practice.

Ideally, our rate of any intervention would live just around the area where the graph takes a hard turn to the right. This allows us to maximize the return on investment, so to speak. I hesitate to use a financial term, but in today’s environment, that is what we really need to do. Most medical interventions in the US are far over-utilized. Because of this, they cause excessive harm (even if they do provide the smallest amount of benefit) and they also cost excessive dollars, driving up the cost of healthcare for no perceptible benefit. In fact, in many cases, once we pass the magical area on the curve, we might actually see worse outcomes (at higher cost), as has happened with cesarean delivery.

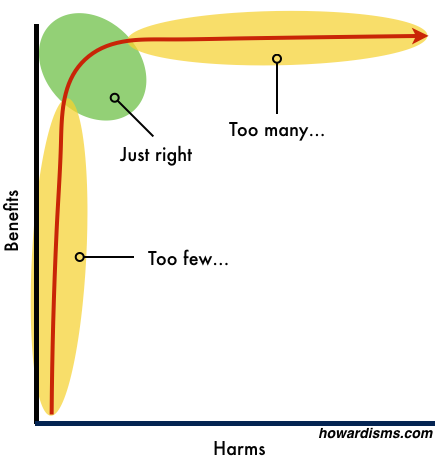

Here’s a way of visualizing the obstetrical interventions listed in the previous graphic:

We need to work to live in the green area and avoid the pendulum swings to either extreme, instead of over-reacting from one tail of the graph to the other. All things in moderation. This all seems rather intuitive, yet we don’t often live in the green world. Why? The Barbell Effect.

Lesson #4: The middle tends to get squeezed out by the extremist positions on either side (the Barbell Effect).

There are a lot of perverse incentives that cause folks to take an extreme position on either side of the “truth.” If you are a doctor, you tend to over-utilize interventions and exaggerate their effects because you make money doing so. Novel and exaggerative research is more likely to get published, so you exaggerate the benefits and minimize the harm. Drug companies and device makers profit from over-utilization, so we see industry-funded research which always shows more favorable results than non-industry-funded research. You get the idea; the whole medical system is primed to live in the far-right area of the above graph.

Many people, rightly, are alarmed and upset at these abuses. They grow tired of constantly-changing medical recommendations, new drugs that hold much promise and then are discovered to not work or have some horrible side-effect, etc. Doctors have created a segment of patients who are and should be distrustful of the medical establishment. But where do they turn for advice? To the equally-exploitive alternative health industry, which stands to make as much money as the medical establishment, but with a lower-cost of entry into the business arena. Literally millions of people in the US take part in this industry, through multilevel marketing schemes or similar efforts.

The result of all this is that most of the attention, time, and dollars are focused on the two extreme positions, leading to the so-called Barbell Effect.

Rather than the margins being marginalized, they are the focus, and they squeeze out legitimate efforts in the middle. The only way to change this is stop focusing on them; stop reacting and over-reacting. Use science and evidence-based medicine in a legitimate way to practice medicine that maximizes benefits and minimizes harms for patients.