Recently, The Guardian reported, in an article entitled Low-risk women urged to avoid hospital birth, on the British National Health Service (NHS) urging low-risk pregnant women to avoid hospital birth in favor of both attached and unattached birth centers and even midwife-led home birth.

There are two questions that this recommendation raises:

- Is this the appropriate decision for women in the UK?

- Is this an appropriate recommendation for women in the US?

The UK decision has already widely been criticized as being a financial one. Here is a UK blogger bemoaning the cuts. And here The Telegraph reported last year about the attempts to save money by the NHS, including cutting maternity services. The NHS is in a financial crisis and shifting nearly half of all birth to lower-cost venues is viewed as a way to save a huge amount of money. While it is guised in the safety issues of having low-risk women avoid interventions (like episiotomies or cesareans), it was pushed through the NHS as a cost-savings effort. Even the piece in The Guardian admits that serious complications for low-risk, first time mothers would be nearly doubled from 5/1,000 to 9/1,000 with such a move, yet the NHS values cost-efficiency above these serious complications. In meaningful terms, using the NHS’s data, the number need to treat (NNT) is 1/250 to reduce serious complications. We generally believe that 1/250 NNT is worthwhile for preventing a serious complication, particularly related to newborns, but it comes at a cost that the NHS can no longer afford.

This is not to minimize the potential harms of hospital-based birth. In the UK, the Cesarean delivery rate has risen to 26% (which is much better than in the US). Many of these are undoubtedly unnecessary, as are most of the episiotomies and other “interventions” that are being over-utilized in low risk pregnancies, both there and here. Yet, the solution to reduce these unnecessary interventions is not to throw the baby out with the bathwater and increase neonatal morbidity and mortality. Of course, the cesarean rate is higher in UK hospitals because they have the half of women who are not considered candidates for non-hospital births and they have all of the transfers from homes and birth-centers which find themselves in need of hospital-based care during the course of their labors. So, some of these comparisons are apples to oranges.

Still, US-based midwife care and UK-based midwife care are vastly different systems. Comparing the two systems is unfair. This has to do with the level of training of our midwives compared to those in the UK, the complexity and integration of the transfer system, and just sheer geography. Most births in the UK, even outside of the hospital, take place within a few minutes of a hospital or birth center. In the US, however, the distance between the home and the hospital can sometimes be measured in hours.

There is also a difference in the values and expectations of patients in the US and UK. In the UK, there is a public debate about the cost-effectiveness of the NHS, and UK citizens are accustomed to the unavailability or rationing of services to save money. People in the US haven’t really experienced this. Yet.

But let’s talk about the second question. Is it appropriate to recommend that US women, who are low-risk, have non-hospital based birth (which would largely be home birth)? Here are some data:

- Johnson and Daviss (2005), in a hugely controversial and biased paper, reported on 5,418 women who underwent midwife supported home birth in North America in the year 2000. They reported a neonatal death rate of 3.32/1000 compared to a death rate of 0.9/1000 in comparable patients in hospitals that same year. Death doesn’t tell the whole story; for every baby who dies, many more will live with permanent injury. They did not report these rates.

- The difference in those mortality rates would represent an excess of 9,000 neonatal deaths that year in the US alone if we largely had a system of home birth. I have written more about this flawed paper here.

- The type of births accounted as low-risk by US-based midwifes is problematic. There is no definition by the American Midwifery Certification Board (AMCB) about what births are acceptable. Grünebaum et al (2015) reported that,

- There were 85,318 home births in the US between 2010-2012, most of which were intentional

- At last 56,140 of these were attended by midwifes, but most of those midwives were not certified nurse midwives

- 1 in 156 of these were twins, 1 in 23 were vaginal births after cesarean, 1 in 135 were breech, and 3 in 10 were beyond 41 weeks

- All of these are excluded as candidates for home birth by most professional societies

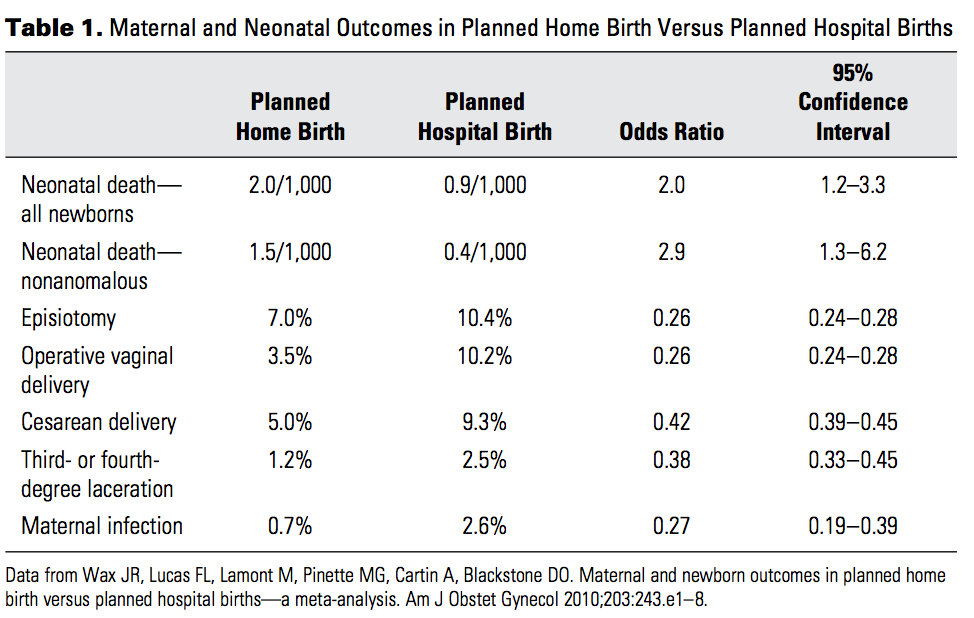

- And how about outcomes of these births? The data below from an ACOG Committee Opinion summarizes a meta-analysis of studies comparing planned home birth vs planned hospital birth.

- These data are consistent with what we have already seen in Johnson and Daviss: a three times higher nonanomalous death rate at home compared to in the hospital. This comes at the expense of more cesareans and more operative deliveries, and maybe too many more, but it’s a value statement really. Is it worth risking a baby’s death to avoid a cesarean. To some people, it may be. Recall that death is only one marker. We have also to consider neurological injuries and other permanent disabilities.

Yet, the problem remains that the US maternity system has serious problems. Maternal mortality has been rising over the last 15 years after spending about 200 years in decline. Cesareans are at an all time high and show signs of climbing still. We invest a lot of money without an appropriate return on investment. Women are increasingly denied the opportunity to have a trial of labor after cesarean, or even to labor with twins. We conduct too many tests and give women too many restrictions. It is a system in need of science-based reformation. Clearly, not all babies need to be delivered in hospitals, but rather than push for home birth, we need to focus on Certified Nurse Midwife-led birthing centers with appropriate back-up for emergencies.

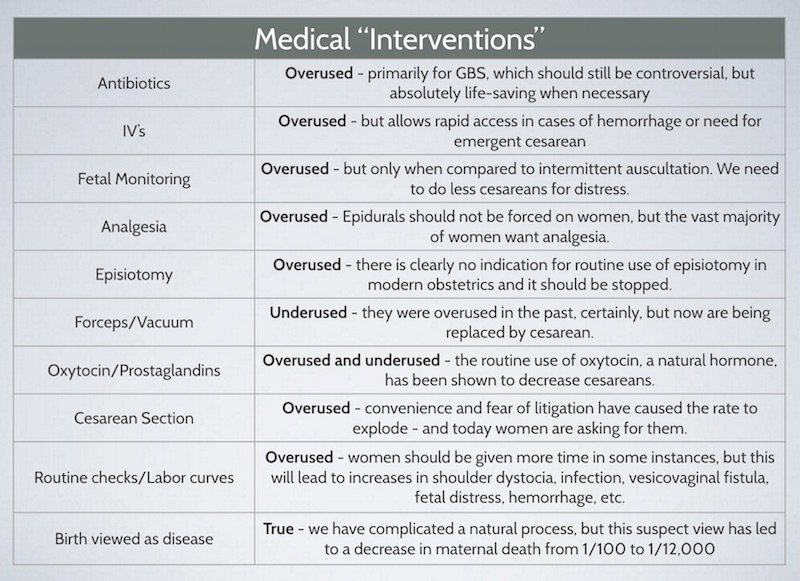

More than this, though, we need to focus on reforming the system that we have. Modern obstetrics has reduced maternal mortality by 99% over the last 150 years! Let’s focus on keeping the good and reforming the bad. A lot of unexpected things can happen during birth:

Our interventions are both good and bad. They are good when they are used to treat or prevent some of these bad things, and a certain amount of over-treatment is necessary. But at some point, they become bad. We must continue to used evidence-based medicine to find the sweet spots, the point of inflection of the Receiver-Operator Curve, where the benefit outweighs the risk.

We can’t force women into dangerous situations, like home VBACs or home twin deliveries, because we refuse to follow evidence-based obstetrics. Women want and deserve choice in their birthing experiences, but they also deserve accurate and scientific information to inform their decisions.