Should we perform prophylactic salpingectomy whenever possible to reduce the risk of ovarian cancer?

Over the last five years, many gynecologists have made it routine practice to perform bilateral salpingectomies at the time of hysterectomy whenever possible to reduce the risk of ovarian cancer, and some have extended this to making bilateral salpingectomies their method of choice for performing sterilizations for the same reason.

This practice started because of evidence that suggested that among BRCA positive women most high-grade serous epithelial ovarian cancers start in the fallopian tube and that prophylactic salpingectomy among these women reduce the risk of the development of ovarian cancer. Based on the idea that such benefits would extend to the general population, and the assumption that there was little to no risk in performing bilateral salpingectomies, the idea of the prophylactic salpingectomy was suggested and seized upon by many thousands of providers without any scientific evidence that the practice was meaningful in women who did not carry a BRCA mutation.

Some skeptics would point out that it is surprising how widespread the practice has become without any robust data that suggests that it works. Further, a skeptical cynic may also point to the fact that the practice of bilateral salpingectomies at the time of hysterectomy or instead of other sterilization procedures results in a significantly larger fee for the surgeon without much added time or work. It is interesting how many evidence-based practices there are which have not been adopted by physicians despite overwhelming scientific data; but many of these practices result in the physician making less money. In the case of prophylactic salpingectomy, physicians are adopting a new practice pattern without robust data but it results in more revenue.

But apart from this very cynical perspective, what do we need to know about the practice of prophylactic salpingectomy? One of the better arguments for the practice of routine bilateral salpingectomy is available here from the February, 2017 edition of Contemporary OB/GYN by Saunders et al. Note that this is the same “journal” that recently reported that homeopathic estrogen was an effective treatment for endometriosis. But we will refer to this review article as a source of the best arguments and data supporting the practice.

Here are the questions we need to consider:

- Are there data suggesting that prophylactic salpingectomy reduces the risk of subsequent development of ovarian cancer? If so, how much risk reduction is there and how does this compare to the known risk reduction associated with tubal ligation or hysterectomy?

- Are there any negatives of performing the procedure itself?

- Are there any drawbacks of recommending routine bilateral prophylactic salpingectomy instead of what we currently offer (or should offer) to patients seeking sterilization?

- If there is a benefit to the policy, is it worth the cost to society?

Before we answer these questions as well as we can, let me summarize the arguments presented in the review article referenced above. Here is the gist of the argument:

- In BRCA-positive women, most high-grade serous epithelial ovarian cancers appear to originate in the fallopian tube.

- At the time of prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy in these women, 5 to 10% have tubal precursors to malignancy (though most of these patients have p53 mutations).

- Bilateral salpingectomy at the time of hysterectomy is safe and cost effective.

- Previous salpingectomy does not appear to affect future ovarian function, whether done for sterilization or at the time of hysterectomy.

- Salpingectomy might also prevent other benign problems with the fallopian tube, including infections, hydrosalpinges, torsion, and ectopic pregnancy.

- Failure rates from traditional sterilization procedures are higher than previously estimated, and as high as 5% among women under age 27 who undergo a bipolar cautery procedure. Bilateral salpingectomy would greatly reduce the number of failures and ectopic pregnancies if performed routinely rather than traditional sterilization procedures.

- Data from a recent Danish study of over 13,000 ovarian cancer patients “confirm that bilateral salpingectomy reduces the risk of epithelial ovarian cancer by 42% (OR 0.58).” Based on the assumption of a number needed to treat of 100, the authors assume that 7000 cases of ovarian cancer in the United States could be prevented each year.

- The authors conclude that all women who are undergoing gynecologic surgery after childbearing is completed or who need sterilization procedures should therefore be given bilateral salpingectomies.

- They conclude with this question: “Why keep an organ with no ongoing physiologic role when it can be safely removed at the time of planned surgery, and leaving it in situ places a woman at risk for a potentially preventable cancer?”

So, let’s try to answer the questions and analyze the nine points of the argument as listed above.

Regarding points 1 and 2: There is indeed good evidence that prophylactic salpingectomy reduces the risk of ovarian cancer development among women with a p53 gene mutation or among women who are BRCA1/2-positive; it seems quite clear that among these groups of women, most high-grade serous epithelial ovarian cancers do indeed start in the fallopian tube. However, data are lacking to indicate if the same is true for women who do not carry a high-risk genetic mutation and it is unfair to extrapolate the magnitude of effect from those high-risk populations and apply it to women of average or low-risk.

The authors answer the question of magnitude of effect in point 7 by referring to a retrospective Danish study by Madsen et al. from 2015. This study represents the only significant effort that I am aware of that addresses the question of benefit from prophylactic salpingectomy in average risk women and it is the only such paper cited by Saunders et al. The article is summarized by the authors in this way: “Recent data from a Danish study of more than 13,000 ovarian cancer cases confirm that BS reduces the risk of epithelial ovarian cancer by 42% (OR 0.58).”

The use of the word “confirm” is rhetorically very interesting; it implies that the 42% reduction was a known figure suggested by other data and reinforced in the current study (it was not and is not) and it also is a very powerful word leaving little room for equivocation or doubt. But with a study of over 13,000 patients, how could there be any doubt? But this is why it’s always important to read the original papers because agenda-driven authors rarely tell the whole picture or include relevant data.

Here are some more details about the study:

- The study of 13,241 women was primarily designed to look at the effect of tubal ligation on prevention of ovarian cancer. 13,135 of the women had undergone tubal ligations and not salpingectomies.

- They found that tubal ligation alone reduced the risk of epithelial ovarian cancer by 13%.

- Most of this reduced risk was associated with endometrioid-type ovarian cancer, with a 34% reduction (likely because the tube serves as a conduit for abnormal endometrial cells to gain access to the ovary), and a 40% reduction in ovarian cancer risk was observed for other unusual pathology types. There was no effect on borderline ovarian tumors.

- Of the over 13,000 women in the study, 89 underwent a unilateral salpingectomy; among these women, there was only a 6% decreased risk of future ovarian cancer development, about half the rate of risk reduction observed among the bilateral tubal ligation group. Perhaps this makes sense since only one tube was interrupted? Still, if salpingectomy carries a greater benefit than simple tubal disruption, then one would presume to find a greater magnitude of effect from unilateral salpingectomy. Indeed, if the bilateral salpingectomy affords 42% risk reduction, then unilateral salpingectomy should afford perhaps a 21% risk reduction; but it did not.

- Finally, among the 13,135 enrolled patients, there were just 17 who underwent bilateral salpingectomies. It is from these mere 17 patients that the meaningless statistic of a 42% reduction in the future ovarian cancer risk is derived. You shouldn’t have to be an expert in statistics to understand that this is a case series at best and not enough patients from which to derive any statistical inferences.

- The authors tell us nothing about the individual 17 patients (for example, the pathology type of the cancers), so we can draw no conclusions about whether the observed risk reduction (which is not statistically significant given the sample size) is different than the risk reduction observed in patients who underwent bilateral tubal ligation alone, particularly for the endometrioid or other type pathologies.

- The authors confirm that no other published data reports on risk reduction of prophylactic salpingectomy in average risk women and they conclude that “Additional studies are needed to establish whether this translates into a potential preventative intervention for epithelial ovarian cancer.”

- One last minor point: Saunders et al. assume that odds ratio (OR) and relative risk (RR) are interchangeable; there is not enough data in the paper to know this. For small numbers (like 17 patients), the OR may exaggerate the RR. So saying that an OR of 0.58 represents a risk reduction of 42% is not precise and may be wrong.

You should feel misled or even lied to given the way Saunders et al. presented this paper. The phrase “more than 13,000 ovarian cancer cases confirm” is academic misconduct at worst and intellectual dishonesty at best. But that statement sounds more convincing than saying “a study of 17 patients showed a nonsignificant and unexplained trend toward fewer cases of ovarian cancer.” How many readers of their review do you think will go read the original article for themselves?

The subsequent conclusion made about the number needed to treat of 100 to prevent a single case of ovarian cancer is entirely based on this insignificant group of 17 women from one retrospective, population-based study from Denmark. In other words, this number needed to treat might as well have been made up.

I have no doubt that salpingectomy does prevent some number of ovarian cancer cases, and I think it is probable that salpingectomy prevents more cases than does tubal ligation alone – but this isn’t known. It is clear that the biggest reduction comes to women with oncogenic mutations and we should diligently be screening for these women in our clinical practices. But for average risk women, we just don’t know the magnitude of effect and it may not vary significantly from the benefit seen with tubal interruption alone. This Danish study actually provides decent evidence that this may be the case in that the rate of ovarian cancer reduction among women with unilateral salpingectomy was about half the rate of ovarian cancer reduction in women undergoing bilateral tubal ligation, implying that the risk reduction from salpingectomy and tubal interruption is proportionate. We must be very careful not to exaggerate the magnitude of benefit that salpingectomy might afford.

Is bilateral salpingectomy safe and does it affect future of ovarian function? The answer to these questions are needed to understand the validity of points 3 and 4 in the Saunders et al. review. On the whole, there do not appear to be any data to suggest that salpingectomy at the time of hysterectomy or compared to tubal ligation is associated with any increased risk of future ovarian dysfunction. That being said, it is not a well-studied area and we don’t know the general applicability of what data we do have to a broad population of gynecologic surgeons. In other words, might a less scrupulous surgeon armed with an energy sealing device cause unnecessary thermal damage to the ovary or its blood supply due to poor technique that is not captured by existing studies? Only time will tell.

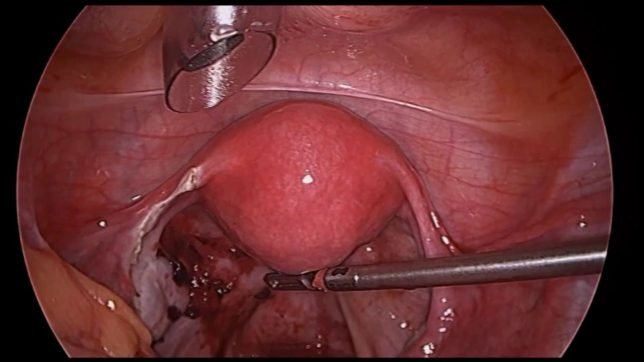

When we discuss the safety of the procedure, we must consider to what procedure we are comparing the safety of bilateral salpingectomy. Most studies have focused on the safety of bilateral salpingectomy at the time of a laparoscopic procedure, either a laparoscopic hysterectomy or a laparoscopic sterilization procedure. But this is a false equivalence fallacy, because neither of those procedures are the best procedures to accomplish their respective goals and, as a community, we should not be encouraging either of those procedures. So, we need to compare the safety of salpingectomy at the time of hysterectomy or as an alternative sterilization procedure to vaginal hysterectomy without salpingectomy (the gold standard procedure) and to hysteroscopic tubal ligation (the gold standard procedure). We know that both vaginal hysterectomy and Essure sterilization are safer and more effective than their laparoscopic equivalents.

In other words, it should not be a question of replacing the laparoscopic tubal ligation with a laparoscopic salpingectomy, it should be a question of replacing a hysteroscopic tubal occlusion with a laparoscopic salpingectomy. This direct data for this comparison does not exist, but we know that laparoscopic sterilization is associated with significantly increased morbidity compared to hysteroscopic sterilization, so it should follow that laparoscopic salpingectomy would as well.

While adding a salpingectomy to a laparoscopic hysterectomy may not be associated with any increased morbidity, we do not know if this is the case with a vaginal hysterectomy and it stands to reason that in many patients, a vaginal salpingectomy could significantly complicate a vaginal hysterectomy. Since vaginal hysterectomy is a markedly better procedure then laparoscopic hysterectomy, then if the desire to perform a bilateral salpingectomy pushes a surgeon towards a laparoscopic rather than a vaginal approach, the patient will have been harmed and cost added.

Point 5 in the review articles relates to the prevention of other benign gynecologic problems like hydrosalpinx by performing a salpingectomy rather than a tubal ligation or by leaving the tube behind at the time of hysterectomy. It is hard to argue with this point, but we should remember that no one has ever argued that these benign pathologies are sufficient reasons alone to remove the tubes. It may be an advantage, but it is a slim one, and this marginal benefit might be outweighed by the risks of doing an unnecessary invasive procedure when a less invasive procedure would have sufficed.

Cost is an issue and I believe that reimbursement is a main motivator of the widespread adoption of prophylactic salpingectomy without robust scientific data to support the procedure. Removing the fallopian tubes at the time of hysterectomy adds an average of 1.7 work reimbursement value units (wRVUs) to each procedure. Performing a laparoscopic salpingectomy as a sterilization procedure reimburses 7 additional wRVUs compared to a traditional tubal ligation and 8 additional wRVUs compared to an Essure procedure. Of course, the total RVUs and facility fees are significantly higher as well. In many practices, removing the fallopian tubes has replaced the traditional reimbursement-boosting practice of unnecessarily removing one or both ovaries. The reimbursement is the same whether you remove the fallopian tube or the ovary and since the practice adds essentially no time to the performance of the case, the added reimbursement is a significant motivator.

Point 6 relates to the issue of high failure rates associated with traditional tubal ligations and the subsequent development of ectopic pregnancies. I especially appreciated the authors’ pointing out that bipolar cautery is associated with a failure rate of as much as 5% when performed in women under the age of 27; they also point out that despite this fact being widely known for many years, gynecologists persist in using this method of sterilization. No one should be doing bipolar cautery as a method of sterilization in 2017 and the fact that the practice is so widespread shows how unscientific the speciality tends to be.

But in pointing out the inadequacies of traditional tubal ligation, the authors failed to ask the more important question: Why are we doing sterilization procedures at all?

The failure rates of the long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs) particularly the medicated IUDs (Mirena, Liletta, Skyla, Kyleena) and the implant (Nexplanon), are dramatically lower than the failure rates of even the best female sterilization procedures (Essure). What’s more, with LARCs, the cost is significantly lower, the risks of surgery and anesthesia are practically nonexistent, and there is no issue with tubal regret and the subsequent need for very expensive interventions like tubal reversal and in vitro fertilization.

Beyond this, the medicated IUDs in particular significantly reduce the risk of endometrial cancer and may reduce the risk of endometrioid-type ovarian cancers in the same way that tubal ligation and salpingectomy do. Also, many women would likely be saved future unnecessary hysterectomies due to abnormal uterine bleeding if their birth control method of choice were a medicated IUD rather than a sterilization procedure. In point of fact, one might argue that it is unethical to perform surgical sterilization in the era of medicated IUDs. What justification is there for offering the woman an invasive procedure with a higher complication and failure rate at a greater cost, and one that is associated with a greater future need of hysterectomy and other gynecologic procedures?

The last point made by Saunders et al. is this:

“Why keep an organ with no ongoing physiologic role when it can be safely removed at the time of planned surgery, and leaving it in situ places a woman at risk for a potentially preventable cancer?”

This was essentially the same argument made for decades about prophylactic appendectomy. At one time, gynecologists performed more appendectomies every year than did general surgeons, removing the little wormlike organ at nearly every hysterectomy and cesarean delivery. It wasn’t until this century that the function of the appendix was finally discovered, though the role of prophylactic appendectomy had long since left OB/GYN. I will also note that gynecologist finally stopped doing appendectomies not because the science suggested that it was of no benefit, but because insurance companies stopped reimbursing for the procedure.

So, what should we do? A counter argument to the points that I’ve made is that it may take another decade before we have convincing evidence about the efficacy of prophylactic salpingectomy. In the meantime, many women may be harmed by a lack of action on our part. I agree with this. It is also possible, though far less likely, that we may discover that women were being unknowingly harmed by prophylactic salpingectomy. Remember, medical history is full of trials of interventions that later turned out to be unnecessary or ineffective. Given this history, is extremely difficult to recommend adoption of a new procedure without any direct scientific evidence of its benefit (do vaginal mesh kits ring a bell?); yet, this is what we are being asked to do.

The real harm of the prophylactic salpingectomy fad is if it encourages people to do procedures that don’t need to be done in the first place, and make doctors feel like those unnecessary procedures are actually a great thing because they are preventing ovarian cancer. Specifically, we should be encouraging decreased utilization of sterilization procedures in favor of long-acting reversible contraceptives; but this current fad has the emotional fervor to do the opposite. Even when sterilization is indicated or preferred by the patient, we risk encouraging physicians to replace a safe and effective office-based hysteroscopic tubal occlusion procedure with a more dangerous and more costly laparoscopic procedure performed under general anesthesia.

The same argument holds for hysterectomy approach. At a time when we should be encouraging more vaginal hysterectomies, when the science and evidence supports that more than 90% of all hysterectomies performed for benign indications can and should be performed vaginally, the emotionally powerful argument of ovarian cancer prevention will be used to motivate gynecologists to perform more laparoscopic and robotic procedures instead.

Prophylactic salpingectomy can be performed vaginally in most cases rather easily; I feel comfortable doing so in the majority of my vaginal surgeries. The residents in training and those less comfortable and adept at vaginal surgery might use the “need” for prophylactic salpingectomy as an excuse to perform an endoscopic procedure instead. They also use it as a selling point of endoscopic surgery. I have already seen patients in my practice, who come to me for a truly minimally invasive vaginal hysterectomy, who have also gone to other gynecologists and were told that they needed a laparoscopic approach rather than a vaginal approach solely for the benefit of removing the fallopian tubes and guaranteeing that the entire tube was removed so that they didn’t get ovarian cancer. That’s quite a stretch! But that’s the type of logic and lack of evidence-based medicine that pervades modern gynecology. We certainly don’t need to teach a whole generation of future gynecologists that it is a necessity to remove the fallopian tube, particularly when not a single study says that it is beneficial yet.

We need to change the discussion from one of prophylactic salpingectomy to prevent ovarian cancer to one of opportunistic salpingectomy to potentially reduce the risk of ovarian cancer. What do I mean by this? Well, if you can remove the fallopian tubes at the time of vaginal hysterectomy, then do so by all means. I have been doing this for some time now. If you cannot remove them, don’t worry about it. Do not change the route of hysterectomy just because you believe it is easier to do a salpingectomy. The real and known benefits of doing a vaginal hysterectomy far out way the theoretical and unproven benefits of doing a salpingectomy.

In the same way, if you happen to be doing a laparoscopic sterilization, then I wouldn’t blame you for removing the fallopian tubes, but you should tell the patient that doing so will cost more money, may not be covered by Medicaid, will be associated with more postoperative pain and longer operative time, and that we currently do not know or understand the benefit to them in reducing the risk of ovarian cancer. That’s informed consent. Perhaps to be truly informed, you should also tell them that you’re going to make more than twice as much money if they consent to salpingectomy and that this fact may influence how you have presented the evidence.

But beyond this, you should be doing your best to convince patients who are interested in sterilization to either get a hysteroscopic sterilization or a long acting reversible contraceptive. The danger of the prophylactic salpingectomy fad is that it encourages providers to abandon other less invasive and more beneficial methods for endoscopic salpingectomy (yes, even robotic salpingectomy). It would be a boon for public health if no woman were sterilized and instead all received long-acting reversible contraceptives.

If gynecologists don’t truly appreciate that there is zero evidence supporting a significant benefit from prophylactic salpingectomy, then we will soon see the numbers of sterilization procedures in the United States triple or quadruple and women who are happy with IUDs will be told that they need to have a prophylactic salpingectomy or they will get ovarian cancer. Again, the trend should be going the other way.

Opportunistic salpingectomy, on the other hand, should be a mere afterthought. After the appropriate and least invasive procedure is selected for the patient, then if salpingectomy can be easily accomplished at the same time, then do it. Until data appears from prospective, randomized trials showing a significant benefit in average risk women from prophylactic salpingectomy, then doing anything more is ludicrous and irresponsible. Large trials are necessary to understand the full spectrum of risk and benefit, including risks we have not discussed like trocar-related bowel and vessel injuries, lawsuits from ovarian cancer patients against their former gynecologists who’ve merely tied their tubes, etc.

Be leery of fads, particularly ones without a single randomized, prospective trial.